NOTHING LIKE A PANDEMIC TO MAKE THE CASE FOR UNIVERSAL HEALTHCARE IN THE U.S.

By Shaghayegh Hanson

The U.S. is the only developed country in the world without a universal health care system. While no country’s healthcare system has been iron-clad against the COVID-19 pandemic, it is becoming increasingly clear that countries similarly large and/or as rich as the U.S. have been better prepared in their mitigation responses because of their universal healthcare systems. Whether voters and politicians, who often harbor misconceptions about a universal system, learn any lessons from this remains to be seen.

To be clear, no one is suggesting that universal healthcare is perfect. For example, in 2018, thousands of people demonstrated in London against the lack of funding for the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS). They held placards that said things like, “Keep your hands off our NHS,” and “Saving lives costs money, Saving money costs lives.” However, Donald Trump seized the moment for his own political purpose, tweeting: “The Democrats are pushing for Universal HealthCare while thousands of people are marching in the UK because their U system is going broke and not working. Dems want to greatly raise taxes for really bad and non-personal medical care. No thanks!”

The swift response to Trump from the ruling Conservative party in the U.K. reflected what all other developed nations in the world know to be true; the Health Secretary wrote: “I may disagree with claims made on that march but not ONE of them wants to live in a system where 28m people have no cover. NHS may have challenges but I’m proud to be from the country that invented universal coverage – where all get care no matter the size of their bank balance.” Since then, the number of uninsured people in the U.S. has risen to approximately 30 million. Another 40 million are underinsured.

Moreover, far from “not working” and being “non-personal,” the NHS has been successfully providing quality healthcare for over 70 years, which is why citizens and politicians of every background are highly protective and proud of the NHS. They willingly pay the taxes required for this service because they understand that, in the long run, it saves them from paying thousands more to insurance companies who may or may not cover them when push comes to shove. Unlike in the U.S., in the U.K., and other countries with a universal healthcare system, no one is afraid of becoming bankrupt in the event of a catastrophic medical emergency, such as being struck by a pandemic.

Just look at what Boris Johnson, the current Conservative party Prime Minister of the U.K. had to say after he was treated for COVID-19 and released from an NHS hospital: “The NHS has saved my life. Our NHS is the beating heart of this country. It is the best of this country. It is unconquerable. It is powered by love.” By this standard, he would be considered a revolutionary in the U.S.

When the virus initially hit the U.S., there were reports of doctors and emergency rooms turning away uninsured and/or underinsured citizens with symptoms. Tens of millions of citizens avoided medical attention, including testing and treatment, for fear of taking on the financial burden. These people went undetected. They became spreaders to all sections of society regardless of income or race.

America’s emergency rooms were already dealing with critical cases that could have been prevented if those patients had access to affordable or free care earlier. According to a Vox news article, “We know Americans delay care as a result of . . . cost barriers: in 2019, 33 percent of Americans said they put off treatment for a medical condition because of the cost; 25 percent said they postponed care for a serious condition. A 2018 study found that even women with breast cancer — a life-threatening diagnosis — would delay care because of the high deductibles on their insurance plan, even for basic services like imaging.” It is hardly surprising that, under these circumstances, a pandemic would compound and highlight these major inequities and inefficiencies in the U.S.’s patchy health care system. One need only look at the preliminary statistics from Michigan, Virginia, Illinois, Minnesota, North Carolina, Arkansas and Louisiana, to see how the virus is disproportionately affecting the African-American community which has long suffered economic insecurity. Many in these low-income communities are dealt a triple-layered blow; they are more vulnerable due to untreated, long-term underlying conditions, they often have essential-service jobs that expose them to the virus on a daily basis, and they are less able to afford testing and treatment.

Trump initially announced that testing for the coronavirus would be free but did not guarantee free treatment. Now, the administration says it plans to use money set aside in the $2 trillion stimulus package, to pay hospitals for treatment of uninsured coronavirus patients. But this money was intended to fund the immediate frontline needs of hospitals. How the funding will actually be allotted in practice in the coming weeks and months is far from certain, and subject to the whims of a president who believes he has total decision-making authority over anything he chooses, and who has fired the Inspector General in charge of overseeing the disbursements of the money. As of the writing of this article, an uninsured San Diego woman, who was tested for the virus after showing symptoms, received a bill for $897.60 from Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla for the service. She thought, as did many, that the tests were to be free. She has since negotiated a reduction of her bill to $700 and is on a payment plan. Apparently, what Trump meant by “free” was that those with insurance would be relieved of their co-payment for testing. Where does that leave the 30 million who have no insurance, people, who arguably, need the monetary assistance even more than those who already have some form of insurance? Why, after all these weeks of strategizing against the spread of this pandemic, is there still a possibility that millions will not be able to afford testing? As the Financial Times put it: “To treat testing as an afterthought risks allowing the coronavirus epidemic to become even more serious that it already is. Effective diagnosis is the bedrock of an effective medical response. Just as much as vaccine development, testing should be considered a vital public good.” In his latest briefing, Governor Cuomo of New York, stated that the “unvarnished truth” was they could not do enough testing which would be the key to reopening the economy.

In the meantime, at the time of this writing, the United States has overtaken Italy as the country with the highest number of coronavirus deaths, that is, 26,334 people (as of this writing). We have 618,893 reported cases and many unreported. 6.6 million people have filed for unemployment benefits. Hospitals and their staff are begging for essential protective gear and other supplies. States are outbidding each other for ventilators. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has said, “It’s like being on eBay, with 50 other states bidding on a ventilator.” Instead of centralizing the purchase of supplies and then distributing according to need, the federal government has joined the auction, with FEMA successfully outbidding some states. The price of ventilators has skyrocketed.

We are all now pinning our hopes on a vaccine against coronavirus, but the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, cannot promise such a vaccine will be affordable to all. Of course, as long as private payment is concerned, it most certainly will not be affordable for some. And with the economy in such bad shape and millions unemployed, the number of those uninsured and underinsured will surely rise, exacerbating the current crisis.

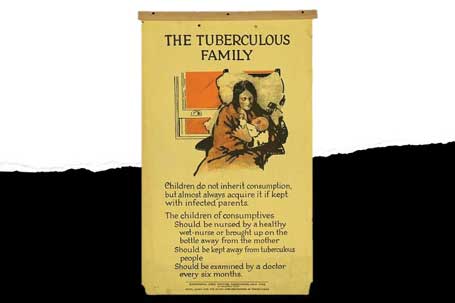

A recent article in Slate magazine reminded readers that when germ theory was first acknowledged in the U.S. in the late-nineteenth and early twenteeth centuries, Progressive Era reformers tried to “convince elites to care more about the health of the poor.” The New York City health commissioner at the time wrote that “[d]isease binds the human race together as with an unbreakable chain.” The novel coronavirus underscores the truth of this statement. The U.S. is learning, the hard way, that universal healthcare is not just a “moral” proposition targeting the poorest of us, but a tool of sound governance that protects all of us.

https://www.marketplace.org/2020/04/01/ventilator-bidding-war-covid19/

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-insurance.htm

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/03/upshot/trump-hospitals-coronavirus.html

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52245690