by Hooshyar Afsar

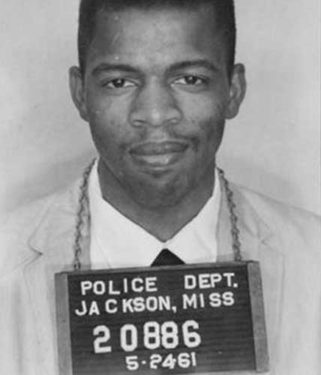

Remembering Congressman John Lewis, Extraordinary Human Rights Defender

Congressman John Lewis, one of the few remaining icons of the Civil Rights Movement, died after a battle with pancreatic cancer on July 17, 2020.

Lewis was born more than 80 years ago to a large family of sharecroppers in Troy, Alabama. He worked hard along with his parents and siblings and found a way to board the school bus even on days that his father told him he couldn’t go to school because his labor was needed on the farm. Lewis used to preach to the chickens when he took care of them and that was good practice for what was coming. At the age of 15, he heard Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech on the radio and he was infected with the inspiration to stand for racial and social justice for the rest of his life.

Lewis was born more than 80 years ago to a large family of sharecroppers in Troy, Alabama. He worked hard along with his parents and siblings and found a way to board the school bus even on days that his father told him he couldn’t go to school because his labor was needed on the farm. Lewis used to preach to the chickens when he took care of them and that was good practice for what was coming. At the age of 15, he heard Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speech on the radio and he was infected with the inspiration to stand for racial and social justice for the rest of his life.

In his first year of college, Lewis embarked upon his activist role by integrating segregated restaurants in Nashville, Tennessee. Even after the Supreme Court ruled various aspects of Jim Crow segregation laws unconstitutional, every gain of the Civil Rights Movement proved difficult. Racist resistance was organized, violent, and vicious. Segregationists poured hot coffee, and extinguished their cigarettes, on students fighting for their human rights. Lewis was not deterred. In 1961, at the age of 21, Lewis was one of 13 original freedom riders who intended to integrate public transportation in the South. Several times he was attacked and injured by white mobs in the Greyhound bus stations. Once, in Birmingham, Alabama, he was left unconscious to die in the station after being beaten by baseball bat wielding white supremacists. Sticking to principles of non-violence, Lewis never responded to violence with violence.

In his first year of college, Lewis embarked upon his activist role by integrating segregated restaurants in Nashville, Tennessee. Even after the Supreme Court ruled various aspects of Jim Crow segregation laws unconstitutional, every gain of the Civil Rights Movement proved difficult. Racist resistance was organized, violent, and vicious. Segregationists poured hot coffee, and extinguished their cigarettes, on students fighting for their human rights. Lewis was not deterred. In 1961, at the age of 21, Lewis was one of 13 original freedom riders who intended to integrate public transportation in the South. Several times he was attacked and injured by white mobs in the Greyhound bus stations. Once, in Birmingham, Alabama, he was left unconscious to die in the station after being beaten by baseball bat wielding white supremacists. Sticking to principles of non-violence, Lewis never responded to violence with violence.

In 1963, Lewis became the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and was the youngest speaker at the historic march in Washington, D.C., in August of that year. His speech was edited by organizers of the March because he had expressed disappointment with the Civil Rights Act that the Kennedy Administration had submitted to Congress. Lewis felt the bill did not go far enough—he wanted police brutality and voting rights addressed as well. Fighting for voting rights in the South, Lewis led the now famous march from Selma to Montgomery in 1965 and was attacked by Alabama state troopers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma that gave him more scars and a fractured skull. Televised images of the attack mobilized national support for the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that passed later that year.

Lewis never stopped fighting for freedom and human rights. He was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1986, representing Atlanta. His untiring stand for racial and social justice earned him the title “Conscience of Congress.” He was arrested forty times in his lifetime, including many arrests after becoming a Congressperson. Lewis was a true defender of immigrant communities and their rights. If the Immigration Bill of 1965, which passed several months after the Voting Rights Act, ushered in a new and more democratic era in U.S. immigration by ending racial quotas, his active opposition to the Muslim Ban left the Iranian American community with an unforgettable sense of gratitude. In February 2017, when Iranians and others arriving in U.S. airports were handcuffed and shackled as a result of Trump’s Muslim Ban, Lewis showed up at the Atlanta International Airport in protest and stayed there way past midnight to make sure all apprehended travelers were released. Later, in March 2018, Lewis honored the Iranian American community in Atlanta by joining a program on racial justice and immigrant community as the keynote speaker. He saw confronting the anti-immigrant policies of the Trump administration as part of the constant struggle for freedom and democracy in this country. That is why he started a sit-in against Trump’s family separation policy on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Lewis never stopped fighting for freedom and human rights. He was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1986, representing Atlanta. His untiring stand for racial and social justice earned him the title “Conscience of Congress.” He was arrested forty times in his lifetime, including many arrests after becoming a Congressperson. Lewis was a true defender of immigrant communities and their rights. If the Immigration Bill of 1965, which passed several months after the Voting Rights Act, ushered in a new and more democratic era in U.S. immigration by ending racial quotas, his active opposition to the Muslim Ban left the Iranian American community with an unforgettable sense of gratitude. In February 2017, when Iranians and others arriving in U.S. airports were handcuffed and shackled as a result of Trump’s Muslim Ban, Lewis showed up at the Atlanta International Airport in protest and stayed there way past midnight to make sure all apprehended travelers were released. Later, in March 2018, Lewis honored the Iranian American community in Atlanta by joining a program on racial justice and immigrant community as the keynote speaker. He saw confronting the anti-immigrant policies of the Trump administration as part of the constant struggle for freedom and democracy in this country. That is why he started a sit-in against Trump’s family separation policy on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Congressman Lewis did not stop fighting for freedom until the last moments of his life. He went to the Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C., before being admitted to the hospital this past June. Two days before he took his last breath, he submitted his last message via an article to The New York Times, to be published after his death. His eternal message for us in that article is: “Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Now that’s a life worth living and that’s a life to learn from.