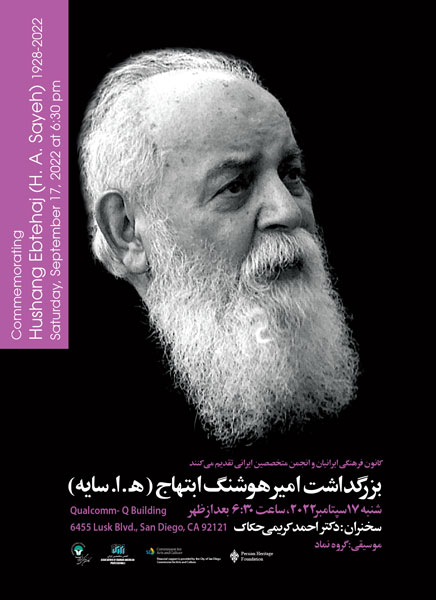

Amir Hushang Ebtehaj—the renowned poet of Iran also known by his pen name, H. A. Sayeh—passed away on August 10, 2022, in Cologne, Germany. Without a doubt he was one of the pillars of Persian literature and will be greatly missed. His works have been translated in many languages, including English.

The following article by Aria Fani was first published in Peyk #143 (Jan-Feb 2013). We thought it would be appropriate to reprint it here. PCC and AIAP will jointly have a commemoration for Sayeh on September 17, 2022, at the Qualcomm Building Q.

Historicity and Romance in the Verse of H. E. Sayeh

Aria Fani

A seasoned traveler on the road to love’s door.

A poem in translation is a linguistic-cultural unit uprooted from its land of origin and replanted in unaccustomed terrain. The most drastic loss consequent to this transfer is perhaps most frequently the poem’s original cadence, its rhyme and meter. The poem’s web of imagery and allusions, various registers, and idiomatic edifice may also all become “domesticated” in the process, its aesthetic force defanged, its voice dehistoricized, its social power dissipated. To what extent can the translator “foreignize” the target language, perhaps beyond its linguistic comfort zone, to accommodate poetics? How high can the ziggurat of footnotes be erected? (The concepts of “domesticating” and “foreignizing” in translation have been developed by Lawrence Venuti.) Writers are unsurprisingly more skeptical than translators. Adunis, the distinguished Syrian poet, deems translation a “betrayal.” The Cuban poet Gustavo Pérez Firmat addresses the issue in ironic fashion:

The fact that I

am writing to you

in English

already falsifies what I

wanted to tell you.

My subject:

how to explain to you that I

don’t belong to English

though I belong nowhere else […]

The Art of Stepping Through Time (Buffalo, N.Y.: White Pine, 2011), a selection of work by the Persian-language poet H. E. Sayeh, is a welcome addition to the slim body of modern Persian literature in translation. Sayeh is the pen name of Houshang Ebtehaj, born in Rasht in 1927. A highly regarded figure on the Iranian literary landscape, a dozen volumes of his poetry were published between 1946 and 1999. A selection edited by M. R. Shafei Kadkani, Ayineh dar Ayineh (Tehran: Nashr-e Chashmeh), was first published in 1990 and is now in its tenth edition. The Art of Stepping Through Time, the first collection of Sayeh’s verse to appear in English, is the result of a collaboration between native English speaker Chad Sweeney, an author of four books of poetry who lives in Redlands, California, and native Persian speaker Mojdeh Marashi, an artist, writer, and translator based in northern California’s Bay Area.

Youth is a shimmering image

The heart eventually lets it go

Startled from sweet morning sleep

Come, my heart, it’s late

Sayeh’s verse profoundly engages aspects of Iranian political history without compromising poetic independence. His love poems, recited with Hafezian lyricism, are among the most treasured works of contemporary Persian poetry. The Art of Stepping Through Time captures the variety of his verse in bright and engaging English. While the original rhyme and meter schemes of Sayeh’s ghazals are lost, the simplicity of these translations, in form and verbiage, create their own music in English. “Musical congruence rather than musical equality”—this is what Marashi and Sweeney have opted for.

They have collaborated on this project for several years, during which their translations appeared in various peer-reviewed literary journals such as Poetry International, Washington Square Journal, and Indiana Review. With more than 50 poems from 12 books, the selection spans half a century of Sayeh’s verse and offers a thorough picture of his literary development through various poetic forms (rubaʿi, ghazal, and sheʿr-e sepid) and modalities (love poems, elegies, politically charged verse).

Love is the heat that multiplies itself

The birth of a birthing cosmos

The translators have not shied away from footnoting mythological and intertextual allusions, providing guidance to curious readers who wish to explore the literary tradition to which Sayeh belongs. For instance, in the poem “Shabikhoon,” translated as “Night Raid,” the literal meaning of the term (night blood) has been footnoted, which brings the alterity of the source language into English, revealing some of Persian’s semantic peculiarities. Though in the same poem, the translators have opted for a more domesticating translation of saghi, rendering it as “wine maid”—close to the conventional translation for the Arabic saqi, “wine server”—which flattens the deeper connotations of the term in Persian literary tradition. (The saghi pours the wholesome wine of life into the empty bowl of the poet. At times he inspires the poet and at other times he serves as a spiritual teacher, the symbol of the existence of the beloved on earth.) Though this collection is not bilingual, each translation is accompanied by the Persian title, which makes locating the original poems easier.

My bed

is the empty shell of loneliness.

You are the pearl

strung from other men’s necks

Sayeh, in his verse and life, has been politically engaged. Active in the communist Tudeh Party, he was imprisoned following the Iranian Revolution of 1979. However, viewing his literary life exclusively through the lens of political historicity is a reductionist endeavor. Through his short introduction, Sweeney alludes to Sayeh’s multilayered identity, namely the literary humanism that emerges from his love poems. He references Hafez be Say-e Sayeh (Tehran: Chashm-e Cheragh, 1994), a colossal undertaking of a comparative, verse-by-verse study of existing versions of Hafez that took Sayeh around the Persian-speaking world. And he highlights some of the challenging aspects of translating Sayeh and provides useful background information on the aesthetic force and social power of his verse. Marashi and Sweeney must be commended for vigorously and critically engaging with Sayeh’s variegated poetics in translation.

ARGHAVAAN

Arghavaan,

my one-blood, my cut branch!

What color is your sky today?

Sunny

or locked in cloud?

In this corner outside of the world

no sun yellows my forehead,

no news arrives from the spring.

All I know is wall,

the dark so close

when I empty my lungs

the air returns against me,

the flight of the eye

stumbles a single step.

A think flame from a sick lamp

is the only storyteller tonight.

My branch catches,

the air, too, is prisoner.

Whatever remains of me

has lost the color of its face.

The sun has not dropped one

glance from the rim of its eye

into the amnesia of this vault.

From quiet oblivion

in whose cold air every candle dies,

a vision of color kindles the mind,

out there, my arghavaan:

my arghavaan is alone,

my arghavaan cries

with this flayed heart

bleeding from the eyes.

Arghavaan,

what is the secret that spring always

arrives carrying our grief?

That every year the sand stains

with the blood of swallows

and over the branded heart heaps

loss onto loss?

Arghavaan, earth’s claw,

grab hold the morning’s robes and ask

the galloping messengers of the sun

when they will cross this black valley.

Arghavaan, hung in clusters of blood-fruit,

at dawn when doves

riot the windowsill of sunrise,

lift my petaled soul

in your fingers,

hoist it to the flight’s watchtowers.

Hurry, the flock is

grieving for captive birds.

Arghavaan—spring’s banner of flowers,

raise your colors!

Become my bleeding poem.

Keep the memory of my loved ones

red on your tongue.

Shout the poem I cannot write!

Arghavaan, my one-blood,

my cut branch.

ارغوان

ارغوان

شاخه ی هم خون جدا مانده ی من

آسمان تو چه رنگ ست امروز؟

آفتابی ست هوا٬

یا گرفته ست هنوز؟

من درین گوشه

که از دنیا بیرون ست٬

آسمانی به سرم نیست

از بهاران خبرم نیست

آنچه می بینم

دیوار است

آه

این سخت سیاه

آنچنان نزدیک ست

که چو بر می کشم از سینه نفس

نفسم را بر می گرداند

ره چنان بسته

که پرواز نگه

در همین یک قدمی می ماند

کور سویی ز چراغی رنجور

قصه پرداز شب ظلمانی ست

نفسم می گیرد

که هوا هم اینجا زندانی ست

هر چه با من اینجا ست

رنگ رخ باخته است

آفتابی هرگز

گوشه ی چشمی هم

بر فراموشی این دخمه نیانداخته است

اندرین گوشه ی خاموش فراموش شده

کز دم سردش هر شمعی خاموش شده

یاد رنگینی در خاطر من

گریه می انگیزد

ارغوانم آنجاست

ارغوانم تنهاست

ارغوانم دارد می گرید

چون دل من که چنین خون آلود

هر دم از دیده فرو میریزد

Direct your questions and comments to Aria @ af@ariafani.com