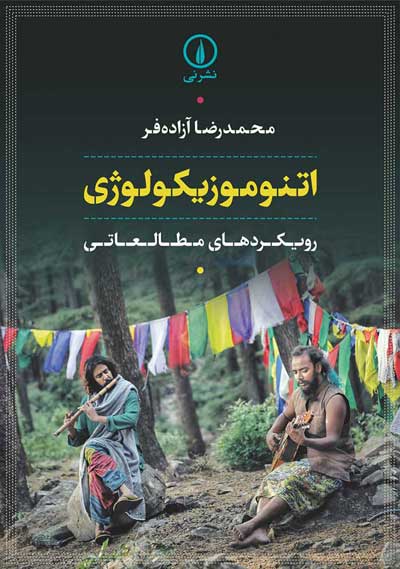

Ethical Research in Ethnomusicology:

Muslim Women’s Ceremonies in Iran

By Vahid Jahandari

Recently, I came across a newly published book, The Routledge Companion to Ethics and Research in Ethnomusicology, composed of a series of articles focused on various aspects of “fieldwork” for music scholars. The various authors delve into the challenges faced by researchers when conducting research while respecting local religious customs and norms.

The Iranian Case Study

One particular case study caught my attention, titled “Good Research versus Ethical Participation at Muslim Women’s Ceremonies in Iran,” authored by Mohammad Reza Azadehfar and Fatemeh Mirtaheri. Dr. Azadehfar, who was once the chair of the music department at Tehran University of Art, where I pursued my undergraduate studies, has been an active scholar and educator. This case study revolves around the authors’ fieldwork-based investigation, first embarked upon in 2018, of the music associated with women’s traditional rites in Iran. The authors acknowledge that analogous complexities arise in other societies where similar ritual settings persist.

Azadehfar and Mirtaheri aim to share their experiences in dealing with the challenges they faced and provide potential solutions that may assist scholars undertaking fieldwork in similar circumstances or those simply curious about ethically examining musical behaviors within the context of semi-private religious ceremonies. They demonstrate how religious values shape social respect and cultural norms, which, in turn, help researchers communicate respectfully with individuals in their ethnographic fieldwork while maintaining academic scholarship standards. Furthermore, the authors examine the focal points researchers should concentrate on to achieve their research objectives while avoiding any harm to the cultural communities or individuals involved in the fieldwork.

The Case Study’s Challenges and Methodologies

Azadehfar and Mirtaheri participated in several Muslim ceremonies to collect religious songs for their research project on sacred ceremonies. While men’s ceremonies are open to both male and female observers, women’s ceremonies are exclusive to women. The authors categorize the women’s ritual ceremonies in Iran, which include solo and group singing, into two main streams: cheerful religious feasts and rites of lamentation. Their participation in and observation of these ceremonies in various parts of Tehran, coupled with interviews with participants, helped them identify behavioral norms that researchers should consider in similar settings. At the forefront of these norms is ethical behavior, which necessitates adherence to traditional procedures underlying each ceremony.

Understanding Cultural and Religious Norms

Learning “proper” behavior, based on the accepted norms of a specific society, often requires years of immersion in everyday life, which can still be limited by gender, race, or ethnicity-based discriminations entrenched in traditions and religious values. I have personally experienced numerous incidents of culture shock during my travels in different countries, encountering differences in cultural norms even within various cities and towns within a single state. By being attentive to personal beliefs and honoring the cultural values of the individuals in the field, however, researchers can develop communal trust, a delicate process influenced by larger socio-economic and political contexts.

Azadehfar and Mirtaheri argue that assuming one can prevent problems in the field by studying religious practices beforehand oversimplifies the issue and can be highly deceptive. The authors provide an example from their study among Muslim communities in Tehran, which revealed significant differences in subcultural issues surrounding ceremonial and ritual practices across various regions of the country. Moreover, the authors explain that in people’s everyday lives, “extra-beliefs” play a more significant role than what might be considered principles of faith by external observers and authorities. In a broader sense, within the densely-populated capital city, there has been more openness in critiquing customs and the origins of certain cultural values and behaviors.

Speaking politely about religious figures and their associated ritual acts is another ethical obligation which presented initial challenges for the authors in their conversations with other participants. They had to avoid causing offense as music scholars since music is considered haraam (wrongful) by some radical religious figures in Islam, although not by all Muslims and not as a law in any Islamic-governed nation. Azadehfar and Mirtaheri mention that during the early periods following the 1979 Islamic revolution, the arts—particularly music—seemed to come to a pause until the late 1990s when new policies allowed greater participation of musicians across the country. They recall instances where they had to be cautious and avoid mentioning music in the presence of believers and new contacts.

Azadehfar and Mirtaheri also emphasize an overlooked or suppressed aspect in research that should be the focus of future studies—the right of researchers to practice their own religious beliefs while living and working in the field. Researchers must navigate the field with two roles: as scholars striving for accurate understanding and representation of behavioral norms, and as human beings aiming to uphold their own dignity and values. The interplay between these two roles may be challenging in some cases, but it can lead to a critical reassessment of one’s ethical values and a deeper understanding of respect at both personal and group levels.

Forging New Relationships

Most of the ceremonies Azadehfar and Mirtaheri studied took place in the private homes of the faithful. To fully immerse themselves in the vibrant musical tapestry of Tehran’s religious communities, the authors realized the importance of developing relationships with new people. They discovered that participation in these communities’ events required joining community groups, which typically originated from existing familial ties and gradually expanded to the formation of friendships. This approach enabled the authors to gain trust, respect, and access to the private ceremonies where music played a role.

Within Tehran’s religious communities, music serves as a powerful vehicle for spiritual expression. Women’s ceremonies, in particular, offer a unique opportunity to witness this profound connection between music and faith. By forging connections with the community, the authors were able to observe and study the various musical practices and rituals that accompany these ceremonies. They discovered that the music played during these events reflected the community’s values, beliefs, and collective experiences, thereby acting as a means to strengthen their spiritual connection.

By engaging with Tehran’s religious communities, Azadehfar and Mirtaheri also recognized the importance of preserving cultural heritage through the study of music. Many traditional musical practices and compositions have been passed down through generations within these communities, contributing to the richness of cultural fabric. Through their ethnomusicology work, the authors actively documented these traditions, thereby playing a role in promoting a heritage from Tehran.

Engaging with religious communities in Tehran also offered Azadehfar and Mirtaheri an opportunity to break down cultural barriers and foster intercultural understanding for an international audience. By developing meaningful relationships, the authors could bridge the gap between their own cultural background and the traditions they sought to study. This cross-cultural exchange allowed for a deeper appreciation and understanding of the religious communities’ music, beliefs, and way of life. It is through such exchanges that ethnomusicologists can contribute to a more interconnected and harmonious world.

The Ethics of Recording

The individuals Azadehfar and Mirtaheri studied during traditional Muslim women’s religious ceremonies generally did not permit the publication of their names or personal details. This aligns with the belief held by devoted performers and participants that, during true worship, one becomes absorbed into God, eliminating the concept of “I.” Therefore, their personal identity is replaced by a group identity and a collective spiritual power that serves as a vehicle for the journey of the soul.

The authors acknowledge that recording performers’ voices was deemed inappropriate and could result in distrust from participants in the future. To overcome this research challenge, the authors propose the involvement of multiple researchers, with each focusing on a single chant to ensure precise recall and transcription after the event. Alternatively, “slow research” conducted over numerous occasions can enable researchers to gradually learn the material. Additionally, Iranian society does not accept women studying as trainee chanters to learn all the songs for research purposes. Training for any other purpose, including education or research, would be seen as unethical, akin to cheating or impersonation. However, participants are comfortable with researchers publishing notations representing the chants, as long as there are no voice recordings, which would expose the beauty of their voices to strangers, akin to the concept of hijab preserving the beauty of their hair.

Azadehfar and Mirtaheri mention being told that their work would be tolerated if they unintentionally overlooked artists with established popular reputations. However, if they ignored figures whom the insiders within these rituals respected, it would be deemed unacceptable. Respect for an individual in this social sector (sacred and cultural ritual) primarily stems from the wider group’s observation of the performer’s actions and conduct. In other words, the people they worked with believed that respect was a result of the collective efforts of musicians and music supporters, as evidenced by how others treat them. However, individual self-respect also holds importance to everyone.

Critique and Takeaways

One of the strengths of this case study is the authors’ personal experiences and their ability to shed light on the complexities of conducting research in a religious and cultural context. Azadehfar and Mirtaheri emphasize the importance of understanding the religious values and social norms of the community they are studying, which is crucial for building trust and maintaining ethical research practices.

However, the case study lacks an analysis of the power dynamics and prejudice that might exist within the research process. The authors briefly mention their position as a couple and how it presented additional challenges, but they do not explore the implications of their own identities and backgrounds on the research process. Understanding the researcher’s positionality is essential for conducting ethical research and ensuring that the findings are not overwhelmingly biased, and plainly shared with readers.

While the authors discuss the complexities of navigating religious practices, they do not address the potential implications of their research on the communities they studied. Ethnomusicology has a long history of researchers extracting and commodifying cultural practices without giving back any tangible benefit to the communities themselves. It would have been beneficial for the authors to discuss how they ensured that their research was respectful and how they contributed to the preservation and empowerment of the communities with whom they engaged.

Additionally, Azadehfar and Mirtaheri briefly mention the historical context of music in Iran, particularly after the Islamic revolution, but they do not delve deeper into the socio-political factors that shape the cultural landscape they are researching, especially under the Islamic Republic, when there is a certain trend and agenda that the regime’s propaganda intends to lead the public perception toward, based on the political climate of the region. A more comprehensive analysis of the broader socio-economic contexts would have shed light on the difficulties that researchers faced in the country.

Overall, “Ethical Participation at Muslim Women’s Ceremonies in Iran” offers valuable insights into the challenges of conducting research in a religious and cultural context when gender plays a critical role in the way in which the research becomes accessible to a global audience under many restrictions. However, further exploration of power dynamics—and reception of their critique among Iranian elites and scholars from the public and private universities in the field—would help with clarifications and/or any revision for review and determining the entire research as authentically and comprehensively as possible for a foreign audience who does not have access to specific examples.

Finally, a more in-depth analysis of the socio-political factors would have enhanced the case study’s overall impact. Power struggle is a regular discourse in higher education and it is worthwhile to capture a better sense of it in relation to religious and cultural ceremonies in Iran. The article sparks ideas for Iranian scholars to invest more resources in researching various forms of public gatherings in today’s Iranian society, especially in larger cities other than the capital city—for instance, Shiraz, Esfahan, and Mashhad—especially considering so much of the past, through the changes of generations, disappears and is therefore no longer accessible for future studies.