Dancing Minds, Knowing Bodies: Rhythmic Revelations through Mindful Movements

By Vahid Jahandari

Sandra Cerny Minton, PhD, a distinguished dance educator and researcher, delves into the connections between dance, mind, and body in her latest work, Rechoreographing Learning: Dance as a Bridge Across the Mind-Body Educational Divide. (1) Drawing on Minton’s expertise, this article provides an overview of her exploration, unraveling the implications for the dynamic interplay between movement and cognition.

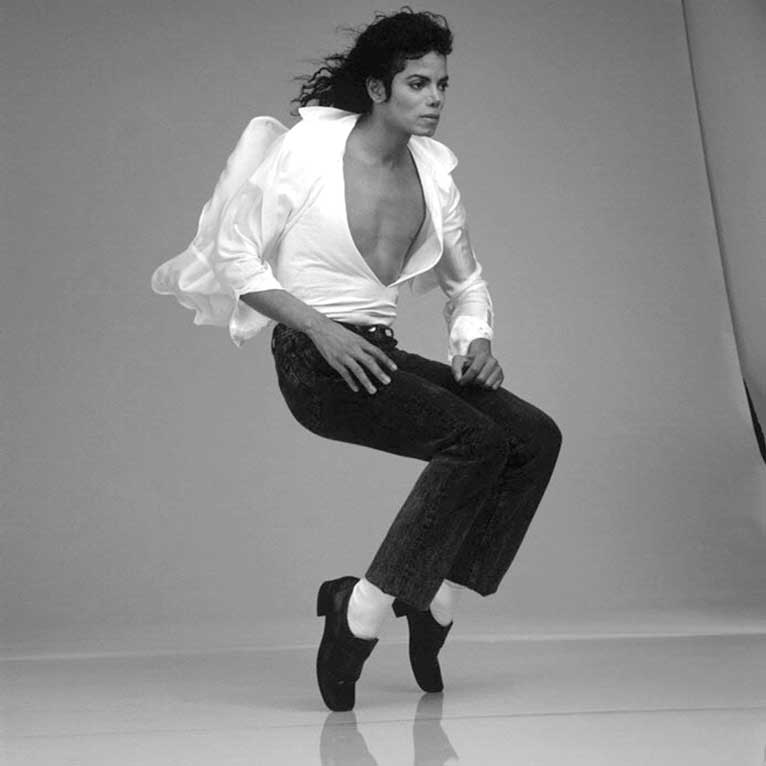

In tandem, I present a case study on Michael Jackson, highlighting his influence that extends beyond the integration of sound and dance for health improvement—a holistic example of artistry and wellness. The inclusion of two additional citations on MJ enhances the depth of my overview, offering perspectives on the sociocultural implications of choreographed auditory processing. Collectively, these insights underscore the profound impact of dance on both our cognitive and physical realms.

Notably, all other citations in this discussion are directly drawn from Minton’s book. As part of her research, Minton has meticulously incorporated numerous references from other researchers, enriching the narrative with a diverse array of perspectives.

Combating the Mind-Body Dichotomy

Beginning with the mind-body dichotomy in the opening chapter, Minton unravels historical hindrances to understanding the bodily basis of knowledge, blending Eastern and Western viewpoints. Shifting to sensory systems, she explores exteroception, proprioception, and interoception, emphasizing their connections to dance. Exteroception shapes sensory experiences by guiding our understanding of the external world, while proprioception provides awareness of the body in motion, coordinating movement (motor actions), and maintaining balance. Interoception enriches our holistic perception by contributing to emotional intelligence and providing data about the body’s internal physiological state. (2)

Minton addresses the prevalent mind-body dichotomy in education, critiquing the overemphasis on cognitive approaches, and highlighting a disregard for the body’s crucial role in achieving holistic educational goals. The chapter delves into the historical context, citing instances where disciplines like mathematics overshadow subjects such as physical education. The passage discusses educators, specifically Alexia Buono, expressing concern about bullying in racially-diversified schools and emphasizing the importance of recognizing the potential role of the body in learning. The focus appears to be on the relationship between child development and teacher pedagogy in the context of early childhood education, without directly addressing issues of racism or sexism. (3)

Minton traces the historical evolution of the mind-body divide, examining influences from Plato to Descartes and Spinoza. Contrasting perspectives from Eastern philosophies, particularly Chinese and Buddhist traditions, emphasize the interconnectedness of the mind and body. (4) The narrative expands to discuss the historical development of Western philosophy on the mind-body connection, contrasting it with Eastern philosophies that integrate the body into their understanding of cognition. The chapter concludes by acknowledging early pioneers, irrespective of their background, who advocated for the importance of the body in understanding the basis of human existence. This concise overview sets the stage for Minton’s subsequent exploration of how dance can bridge the mind-body educational divide.

Cultivating Embodied Learning

Chapter 3 of Minton’s work explores the connections between the body, brain, mind, and thinking, emphasizing the “Body Way of Knowing.” The concept of body awareness is examined across disciplines, revealing varied perspectives. Occupational therapy professor Karen Hebert associates body awareness with an enhanced ability to perceive bodily sensations. Perceptual and motor skills experts describe it as a subjective experience related to physical stability and well-being, shaped by physiological perceptions. Physical educator Heléne Bergentoft provides a multifaceted description, including interactions with the environment, attention to internal sensations, and recognition of body part positions. (5)

In the realm of physical education, researchers distinguish between pre-reflective and reflective body awareness, with a focus on kinesthetic sensations during skilled performance. Minton’s third chapter explores somatic practices, which prioritize sensitivity to the body and conscious awareness. Somatic exercises aim to amplify oneself through kinesthetic sense awakening. Somatics also draw from non-Western influences, with significant input from Eastern practices like yoga, tai chi, and judo, as well as African dance traditions.(6) The chapter underscores the impact of somatics on various domains, noting its benefits for musicians and its application to improve physical functioning and balance. It concludes by highlighting the influence of African movement practices on somatics development in the West, acknowledging the distinct delivery across cultures. (7)

Dancing Across Cultures

In the performance “From Blackness to Gabon-ness: Michael Anicet’s Gabonization of Michael Jackson,” Michael Anicet blends Michael Jackson’s dance style with Gabonese culture. Using traditional elements like raffia garments, he incorporates lingwala dance moves and improvisations inspired by Gabonese dances. The choreography diverges from Jackson’s style, introducing afro-contemporary elements with dancers in wax trousers. Anicet pays homage to Jackson’s iconic scenes with African and Native American dancers. The performance culminates in a human pyramid, symbolizing the fusion of diverse cultural elements and Anicet’s efforts to ‘Gabonize’ Jackson’s dance style. (8) African movement practices shaping somatics align with Michael Anicet blending Jackson’s dance with Gabonese culture. Both show how diverse influences affect body awareness and somatic applications.

Dance, as showcased in Michael Jackson’s transformative short film “Black or White,” goes beyond entertainment to explore profound racial themes. The iconic “panther dance” segment, despite initial criticism, becomes pivotal in understanding the challenges faced by Black artists. Jackson’s dance disrupts traditional norms, offering a gritty exploration of racial complexities. This dance sequence, akin to the dream ballet concept, challenges expectations of white normativity, reflecting broader issues encountered by Black artists. The exploration of Black dreams through dance provides a powerful commentary on the dual consciousness experienced by Black performers in navigating racial dynamics through their artistic expression in America. (9)

A Lens on Human Connectivity

Minton’s fourth chapter delves into the intricate dynamics of the body’s role in shaping interpersonal connections and communication. It opens with a reflection on the collective nature of humanity, often overshadowed by the pursuit of individuality, particularly highlighted during the global COVID-19 pandemic and debates around personal choices like vaccination. Zaretta Hammond’s insights from “Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain” form a cornerstone, urging readers to view individuality and personal choice through a cultural lens. Hammond introduces the concept of cultural archetypes, emphasizing common values and worldviews beneath surface differences. The shift from collectivism to individualism is explored, mirroring the broader cultural shift from urbanization. (10)

The chapter also explores the contemporary multicultural landscape, emphasizing the increasing interconnections between cultures, often accompanied by a lack of understanding leading to suspicion. Sara Konrath’s findings on declining empathy levels underscore the need for cultivating understanding and empathy between individuals and cultures.(11) A detailed exploration of empathy follows, tracing its evolution from a physical to an emotional experience. Rebecca Detrick’s definition of empathy as a visceral response to shared human experiences adds nuance. The distinction between affective and cognitive empathy is discussed, emphasizing the role of abstract thinking in empathy development, typically around the age of 12. (12)

Dancing Emotional Regulation

The narrative of Minton’s book shifts to the teachability of empathy, exploring various approaches and educational literature advocating for empathy as a trait transcending curricular content. The importance of active listening, validation of others’ feelings, and shedding cultural stereotypes for empathy development are highlighted. Chapter 4 seamlessly transitions into the realm of Social-Emotional Learning (SEL), underlining its significance in childhood development. The components of SEL as defined by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)—self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making—are dissected for their interconnectedness with empathy. (13)

Various methods for enhancing students’ SEL abilities are explored, ranging from stress management through mindfulness to collaborative goal-setting. The SPARK program’s effectiveness in promoting SEL principles is discussed, revealing significant positive outcomes. The narrative then unfolds to examine the intersection of movement, dance, and SEL. Physical education programs are proposed as a means to improve students’ SEL skills, with a detailed model of teaching personal social responsibility (TPSR) presented. The importance of understanding SEL language is emphasized, and the impact of dance on emotional intelligence is scrutinized. (14)

Studies on the relationship between movement, dance, and SEL further illuminate the potential benefits. These studies reveal that organized sound processing, along with constructive body movement, can enhance self-management and communication and relationship skills in students. The strong connection between auditive treatment, physical movement, and emotional expression is underscored, with creative dance positioned as a potent tool for emotional regulation. Case studies, such as the New York schools’ dance-based SEL program, provide practical examples of successful integration.

Active Learning through Movement Integration

In Chapter 5 of Minton’s book, active learning, as advocated by Charles Bonwell and James Eisen, emphasizes student involvement and participation, proving more effective than passive listening. This contrasts with traditional methods where teachers dominate the conversation. Recognizing the importance of movement in our constantly-evolving society, educators believe that incorporating daily movement, discussion, and collaboration in classrooms aligns with the natural inclination of our brains. Several learning theories integrate movement and dance as effective teaching strategies, including the zone of proximal development (ZPD), learning styles, multiple intelligences, experiential learning, cooperative learning, and brain-based learning. Lev Vygotsky’s ZPD emphasizes the space between a student’s current development level and their potential learning with proper guidance.(15)

Tailoring lessons to individual factors like emotions, self-confidence, learning style, and attention span is crucial. Scaffolding, or providing temporary support, allows students to reach their upper ZPD levels and accomplish challenging tasks. In a dance context, understanding ZPD can be applied to create movement lessons that cater to students at different cognitive levels. For example, younger students can focus on single movements related to concepts, while older students collaborate on more complex sequences tied to academic content.

Dancing Beyond Boundaries

As Chapter 5 unfolds, David Kolb’s conceptual analysis categorizes learners into convergers, divergers, accommodators, and assimilators based on thinking, feeling, doing, and watching preferences. Incorporating these styles into dance education allows tailoring instruction to individual preferences. Visual learners benefit from demonstrations, auditory learners thrive in discussions, and tactile-kinesthetic learners grasp concepts through movement. Dance education can embrace linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, visual/spatial, bodily/kinesthetic, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and naturalistic intelligence to create lessons that resonate with diverse students.

In dance education, this approach encourages movement exploration, creative expression, and self-directed learning. Cooperative learning fosters collaboration and group work, promoting social interaction in the learning process. In dance education, group choreography projects, collaborative performances, and peer feedback sessions, technical and creative skills are enhanced while teamwork and communication develops. Aligning with how the brain processes information, brain-based learning incorporates neuroscience findings into teaching strategies that optimize cognitive functioning. This involves designing lessons with varied and dynamic movement patterns, sensory stimulation, and a positive atmosphere to enhance cognitive development.

Dancing Holistic Growth

In conclusion, exploring the mind-body connection underscores dance’s vital role in education. Insights into depersonalization and collaborative research emphasize the need for engagement from diverse stakeholders. Additionally, integrating dance aligns with principles emphasizing understanding over memorization, as discussed by scholars. Educational neuroscience further reinforces the interconnectedness of body, movement, and cognition. Insights from neurologists and cognitive neuroscientists highlight the role of movement in pattern recognition, creative problem-solving, and empathy. Positive perceptions of dance by nondance familiars, along with beliefs from classroom teachers regarding creativity in dance, provide evidence of multifaceted benefits. Embracing dance in education aligns with the evolving understanding of the mind-body connection, offering a holistic approach that enhances creativity, social skills, adaptability, and observational abilities among students.

1- Minton, Sandra Cerny. 2023. Rechoreographing Learning: Dance as a Way to Bridge the Mind-Body Divide in Education. Abingdon, Oxon; Routledge.

2- Bailey, Richard. “Educating with Brain, Body and World Together.” Interchange, vol. 51, 2020, pp. 277–91.

3- Buono, Alexia. “Interweaving a Mindfully Somatice Pedagogy into an Early Childhood Classroom.” Pedagogies: An International Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, 2019, pp. 150–68.

4- Sacamano, James, and Jennifer Altman. “Beyond Mindfulness: Buddha Nature and the Four Postures in Psychotherapy.” Journal of Religion and Health, vol. 55, no. 5, 2016, pp. 1585–95.

5- Bergentoft, Heléne. “Running: A Way to Increase Body Awareness in Secondary School Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review, vol. 26, no. 1, 2020, pp. 3–21.

6- Banks, Ojeya Cruz. “Stories of West African and House Dance Pedagogies: 4E Cognition Meet Rhythmic Virtuosity.” Journal of Dance Education, vol. 21, no. 3, 2021, pp. 176–82.

7- Eddy, Martha. Mindful Movement: The Evolution of the Somatic Arts and Conscious Action. Intellect, 2017.

8- Alice, Aterianus-Owanga. 2019. “‘They Don’t Care about Us’: Representing the Black Postcolonial Subject through the Appropriation of Michael Jackson in Gabonese Urban Dance.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 31 (3): 369–84.

9- Chin, Elizabeth. 2011. “Michael Jackson’s Panther Dance: Double Consciousness and the Uncanny Business of Performing While Black: Michael Jackson’s Panther Dance.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 23 (1): 58–74.

10- Hammond, Zaretta. Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin, 2015.

11- de Souza, Marian. “The Empathetic Mind: The Essence of Human Spirituality.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, vol. 19, no. 1, 2014, pp. 45–54.

12- Detrick, Rebecca. “All the Feelings: Seeking to Understand Empathy.” California English, vol. 23, no. 2, 2017, pp. 6–7.

13- Buck-Pavlick, Helen. “Using Empathy and Somatics in Dance Class to Engage Early Adolescent Learners from Low Socioeconomic Communities.” Dance Education in Practice, vol. 6, no. 1, 2020, pp. 20–24.

14- Olive, Caitlin, et al. “Promoting Social-Emotional Learning Through Physical Activity.” Strategies, vol. 34, no. 5, 2021, pp. 20–24.

15- Minton, Sandra. Using Movement to Teach Academics: The Mind and Body as One Entity. Rowman & Littlefield, 2008.

16- Schenkman, Margaret, et al. Clinical Neuroscience for Rehabilitation. Pearson Education, 2013.

To learn more about Vahid Jahandari, visit vahidjahandariofficial.com.