By Aria Fani

In 2013, I wrote an essay in Peyk in which I examined border militarization as a political phenomenon in the United States and Israel. In it, I argued that in both countries, border militarization is rooted in the destruction of land and the dehumanization of indigenous communities. What had given occasion to this essay was the fact that the US Congress had passed a massive budget to further militarize the border and it was signed into law by Barack Obama. Six years later, we have an openly xenophobic president in the White House who ran a presidential campaign based on a promised border wall. In reprinting this essay, I would like to point your attention to the ways in which our inhumane immigration laws predate the current administration. In order to fight for a more humane and inclusive immigration system, we must understand that the current administration has only inherited and dramatically intensified cruel policies that were already in place in previous administrations, policies that were implemented on an institutional level by presidents who even paid lip service to the idea of inclusion and justice.

No Wall Is High Enough!

Policies and politics of apartheid from Berlin to Jerusalem

“Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state, [and] the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country”—Article 13, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 not only cut Germany into two political entities, it also segregated the country culturally, socially, and economically. It split families, lovers, friends. In 1987, two years before its fall, President Ronald Reagan famously challenged Mikhail Gorbachev—General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union—to “tear down this wall,” in a speech made at the Brandenburg Gate. Reagan remarked, “Mr. Gorbachev, we welcome change and openness; for we believe that freedom and security go together, that the advance of human liberty can only strengthen the cause of world peace.” Having been reduced to countless pieces, today the Berlin Wall tours the world, from one exhibition to another, reminding us of the concrete reality of a polarized world marked by policies and politics of segregation.

Like its existence, the Berlin Wall’s collapse in that momentous November in 1989 also became an enduring symbol, one for tolerance and freedom, a fall that was internationally celebrated. Time may have eventually chipped away at the Berlin Wall, but its legacy persists even more powerfully today. It is no longer in the Brandenburg Gate, but rather elsewhere where President Reagan’s words resonate today: Qalandia, Bethlehem, Jenin, Erez, Rafah, Tijuana, Nogales, Reynosa, Agua Prieta. This time, however, much more than a call for “change and openness” ties us—as Americans—to the barriers that stand between Palestine and Israel, Mexico and the United States. These Walls are rooted in our political intolerance; they marginalize and terrorize indigenous peoples, tear communities apart, disturb ecosystems, feed the industry of fear, and destroy the identity of landscapes. They enable policies and politics of apartheid.

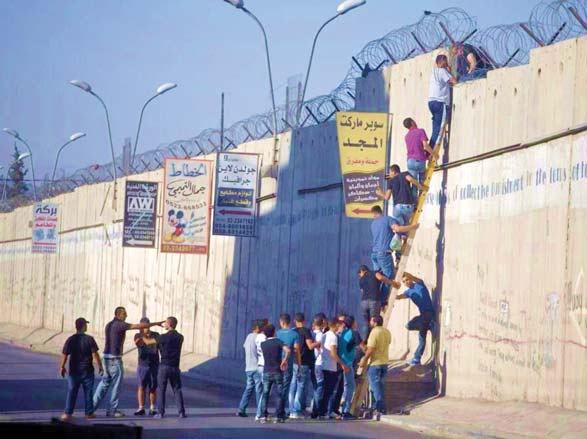

Let us start in Palestine. Funded by U.S. taxpayers, the construction of the Israeli Wall began more than a decade ago. At its core, it isolates the West Bank from historic Palestine—the State of Israel today—where twenty percent of the population is Palestinian. The Israeli Wall is 450 miles long—the distance from San Diego to San Francisco—and stands 26 feet tall, more than twice as high as the Berlin Wall. It is called the “Security Fence” by Israel and the “Apartheid Wall” by Palestinians. The Israeli Wall functions through an advanced and multifaceted security infrastructure: watchtowers, cameras, sensors, electronic fences, and barbwires. While it is important to consider official narratives—political statements and opinions—overlooking the stories of ordinary Palestinians on the ground would only highlight, strengthen, and extend the existence of the Israeli Wall not only as a physical barrier but also as a metaphor for segregation.

My summer plan to study Arabic language and literature took me to Palestine where I witnessed the impact of the Israeli Wall up-close and personally. The Wall’s immediate impact has been on the Palestinian landscape, uprooting thousands of trees and creating a prison-like environment that disheartens and terrorizes locals and intimidates undetermined visitors. For instance, Qalandia, once a small charming village near Ramallah, has been transformed into an open-prison compound: a military base with multiple watchtowers, a checkpoint equipped with revolving doors and fingerprint scanners, an area filled with Jerusalem-bound serveeces, and ambulances on standby in case of clashes between Palestinian youth and the IDF. Qalandia is no longer; it is al-maʿbar, the crossing, al-hajiz, the checkpoint.

The Israeli Wall prevents thousands of Palestinians from reaching their workplaces, schools, farmlands, and hospitals while it curtails their access to the hub of Palestinian life and economy in East Jerusalem. From many parts of Abu Dis, a town in East Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock in the Old City is visible; a distance previously covered in several minutes now takes more than an hour. In Salfit, central West Bank, the property of Mr. Hani Amer has been entirely enclosed by all sides; the Wall, electronic fence, and the Elkana settlement surround his property. He has been entirely isolated from the nearby village of Masah. For months, Mr. Amer and his family were only allowed to leave their house two times a day; he was only recently able to get a key to his own property. Having resorted to humor, the entrance to his house reads: “Welcome to the State of Hani Amer.”

In Bethlehem, the Israeli Wall has shut down businesses and separated families from each other. In one of the neighborhoods, it surrounds a house on all three sides; the family is not allowed to use their rooftop or keep its blinds open due to the Wall’s proximity to their house. The Wall has also been turned into a mural by Palestinian and international graffiti artists and painters. Many residential areas have lost their sense of privacy as tourists pour into Bethlehem to capture the graffiti art or leave their own mark. In the most infamous case yet, Qalqilia, a city northwest of the West Bank, has been entirely enclosed by the Wall; there are only two crossings for thousands of residents. Families who live near the Wall no longer see the sun set or rise. All over the West Bank, farmers’ access to their properties has been severed; many have to walk several kilometers to get to their farm while others have to wait for soldiers to open the gate and allow them in only a few times a day. Many have abandoned their lands.

Referring to an approximately twenty-five foot tall structure as a “fence,” Israel says the Wall merely serves security objectives, and has stopped waves of suicide attacks that target its citizens. Many Palestinians point out that the majority of suicide bombers have come from within Israel—namely Nazareth. It is needless to say that the Wall is not entirely built on the 1967 borders—the Green Line—and consequently has grabbed eleven percent of Palestinian land. Like most walls—in spite of billions of dollars spent on its construction and surveillance infrastructure—the Israeli Wall is incapable of keeping out all “intruders.” Infiltrators (2012), an award-winning documentary directed by Khaled Jarrar, follows several groups of Palestinians in their adventure to sneak through the Wall and into East Jerusalem. Some pay individuals who are familiar with the Wall’s gaps, hoping to end up somewhere safe and unguarded on the “other side.” The Israeli government has not attempted to fill these gaps which raises the question whether the Wall serves security measures3.

The Israeli Wall is an extension of Israel’s policies and politics of apartheid; it is only a part of Israel’s ruling apparatus in the Occupied Territories. While half a million Jewish settlers are connected to Israel via Jewish-only fast roads, West Bankers face traveling restrictions and more fragmentation of their land every day through settlements, settler roads, military bases, trenches, roadblocks, walls, fences, barbwire, tunnels, etc. Interactions between Jewish and Arab populations have been minimized as a result of the concrete barriers that separate communities. For instance, many Israelis went to Masah, a village in Salfit, to buy its quality, inexpensive furniture. According to NPR, “[n]ow Palestinians must carry goods over barricades installed by the Israeli army, and business is drying up2.” Overall, militarization of the West Bank indiscriminately terrorizes and humiliates thousands and millions of Palestinians on a daily basis while relying on acts of violent resistance to justify its existence on the grounds of “national security.”

“We’ll be the most militarized border since the fall of the Berlin Wall. That’s why I think this amendment was very important”—Senator John McCain, June 2013

Located in different terrain, the U.S.-Mexico barriers narrate similar stories, reveal identical scars. Erecting a series of barriers along the U.S. border with Mexico has been one of the main strategies of the U.S. government to combat “illegal immigration and terrorism,” most particularly since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Ten feet tall, the first phase of the barrier in California—coded “Operation Gatekeeper”—started in 1993 along the Pacific Ocean to the Otay Port of Entry. Later, surveillance cameras and stadium lights were added and the barrier was expanded. In 2006, President George W. Bush signed “The Secure Fence Act of 2006” into law, remarking that “this bill will help protect the American people. This bill will make our borders more secure. It is an important step toward immigration reform.” Just recently in June 2013, the Senate passed a comprehensive immigration bill which constitutes the construction of 700 miles of new fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border.

The destructive impact of barriers on communities and ecosystems demonstrates the existing disconnect between the air-conditioned chambers of the United States Capitol and the natural and social landscapes devastated by such policies. Exempted from following environmental regulations, the Department of Homeland Security acts based on what it deems “security measures.” For decades, environmentalists have been expressing concern that putting up barriers across the border is disturbing ecosystems and endangering animal species. The barriers cut through wildlife preserves, private property, and state and national parks. Hundreds of pages of research by Mexican and American environmentalists reflect the devastating impact of these barriers on hundreds of plants and animals, but the U.S. government does not seem to base any of its border conclusions on a serious consideration of such studies.

As in the case of Palestine, the U.S.-Mexico barriers are incapable of stopping people from entering the “other side.” But they are capable of endangering the lives of migrant workers—indigenous to this region—by driving them deep into the desert; many die of dehydration. Further militarization of the border will affect six million people who call the border their home in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, as well as thousands of migrant workers who have been living and working in the United States for many decades and wish to visit their families. According to the Department of State, Mexico is Texas’ number one trading partner and the third trading partner for the country at large; such policies will not only alienate an important economical partner, but also darken social relations with our southern neighbor. While San Diego is inaccessible to Mexican and Central American immigrants, Tijuana, Mexico’s third largest municipality, remains welcoming to thousands of Americans who visit each week for work, entertainment, or medical tourism, as well as hundreds of displaced workers who seek shelter having been deported from the United States.

The U.S.-Mexico barriers have torn indigenous communities apart by driving a physical block between them, forever transforming the identity of their landscape. Friendship Park is an example; dedicated by Pat Nixon, it was built in 1971 on San Diego hills to foster relations between the U.S. and Mexico. Then, only barbed fence marked the border; now the Department of Homeland Security has built a wall: a twenty-foot tall steel barrier with metal posts that continue into the ocean. Once a place for friends and families to come and socialize with each other from both sides, in recent years, free access to the Park has been rare. Jill Hoslin, a professor at San Diego State University, describes these changes: the DHS “blocked off Friendship Park, and suddenly Sundays felt like visiting day at a maximum security prison.” After months of negotiations with San Diego Sector Border Patrol, the Park is now open to the public on weekends. A barrier built to prevent illegal immigration has itself crossed many borders, communities, and families. One frontier, All frontiers (2010), a documentary film by David Pablos, highlights how Mexicans have integrated the border wall into their daily lives, trying to overcome its primary function, segregation, by developing new relationships with their loved ones who live on the “other side.”

You may ask, what connects the Israeli Wall in Palestine to the U.S.-Mexico barriers? Both Walls have been constructed on the destruction of landscape and community life, and neither Wall has taken into account the existence and needs of people whose lives are affected. Both barriers obscure critical issues that have remained unaddressed and unresolved: in the case of Palestine, Israel’s almost half a century-old military occupation, and in Mexico’s case, the corporate-building policies of NAFTA, lack of labor and civil rights for migrant workers, and the U.S. support for the “War on Drugs” that has consumed the lives of more than 40,000 Mexicans since 2006. Both Walls have been born as a result of xenophobic climates against indigenous peoples and feed the billion-dollar industry of border control. In fact, Elbit Systems Ltd., a defense electronics manufacturer based in Haifa, Israel, has been given a multi-billion dollar contract to build the surveillance mechanisms of the U.S. border wall; this is the same company that enables the Israeli occupation to control the movement of millions of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. The spirit of the Berlin Wall lives on through the Israeli Wall and the U.S-Mexico barriers. Qalandia Crossing will one day follow the fate of Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie, reduced to a replica built for curious tourists, a glimpse into Israel’s historic apartheid. With each immigrant who jumps over the U.S.-Mexico barrier, the policies and politics of apartheid that marginalize indigenous populations and rely on xenophobia and criminality to feed the cynical industry of border control will be increasingly clear. As Americans, we are tied to these Walls; as humans, to every wall.

Notes:

1. Title extracted from President Obama’s speech in Jerusalem in March 2013.

2. Source: www.npr.org/news/specials/mideast/galleries/kenyon/settlement/020529.kenyon3.html

3. A student at Birzeit University shared with me that an IDF soldier spotted her after she crossed under a hole into Israel from Al-Ram, north of Jerusalem, but did not attempt to stop or chase her.

Photo credit for the Israeli Wall in the West Bank, Aria Fani; for West Bankers jumping over the Israeli Wall, Oren Ziv; the coast of San Diego-Tijuana, John Gibbins; and for hands and the fence, David Maung.

A native of Iran, Aria Fani has spent time living and studying in Palestine and Mexico. Aria holds a PhD in Near Eastern Studies from the University of California, Berkeley.