Analyzing the complexities of Iranian American racial identity and ensuring an accurate representation of the Iranian American community on the census.

By Shaghayegh Hanson and Lily Mojdehi

To be questioned, to be questionable, sometimes can feel like a residence: a question becomes something you reside in. To reside in a question can feel like not being where you are at. Not from here, not? Or maybe to become not is to be wrapped up by an assertion. To be asked “Where are you from?” is a way of being told you are not from here. The questioning, the interrogation, can stop only when you have explained yourself. –Sara Ahmed

“What are you?” is a question many Iranian Americans are quite used to answering. It is a subtle way of asking, “I can’t figure out where you are from, just by looking at you, what is your ethnic or racial background?” Many of my friends and I could list all the different ethnicities people have asked or assumed we are, such as Mexican, Russian, Italian, Hawaiian, Black, or Spanish, and the list goes on. Not only are many people uncertain about what racial features constitute a person from the Middle East, but also “Middle Eastern” is not an official legal racial category. These two factors cause confusion for both the outsiders who view Iranians , and for the insiders of the Iranian American community.

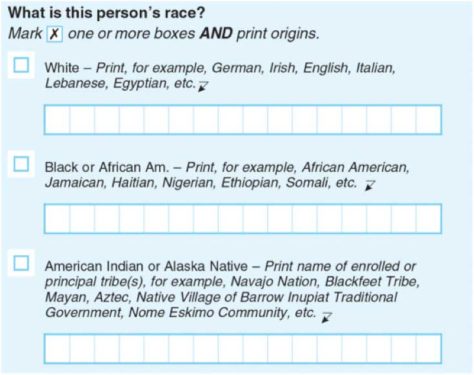

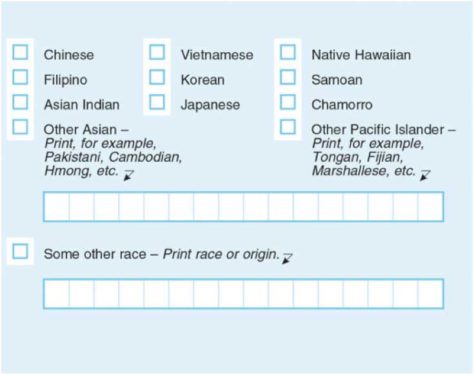

This year, the United States Census will turn the answer to the question of who we are into an official mandate, which is again stirring up the debate about “whiteness.” The census questionnaires will begin arriving in our mail in March and will contain the following answer categories:

The choice, then, for Iranian Americans appears to be “white” or “other.” Historically, first-generation Iranian Americans have been comfortable identifying as white. Most Iranian Americans successfully integrated into American white hegemonic society by accessing education, which led to economic prosperity and, therefore, social capital. Also, many Iranian immigrants—mostly first generations—self-identify as Aryan. The Pahlavi regime in Iran (1925 to 1979) was motivated to compete with powerful Western forces and had therefore established laws and policies promoting a culture of secularization and modernization. In order to support and propagate the idea that Iran was a powerful nation, the Pahlavi regime required all schools to teach a history which states that European people originated from the Persian Empire and Iranians used to look like fair skinned and light eyed Europeans. The regime’s narrative—that Iranians are all descendants of the Aryan people, an idea that was disseminated for 54 years—could have possibly been ingrained in the first-generation Iranians who immigrated to the U.S. conceiving of their racial identity as nothing but “white.”

However, in the last decade, more studies, articles, and books have catalogued the growing dissatisfaction Iranian Americans, especially younger generations, feel about being categorized as “white.” The evolution of this sentiment can be traced through political events that have contributed to the racialization of Iranian Americans and other Middle Eastern communities in the U.S., such as The Iran Hostage Crisis in 1979, the September 11 attacks in 2001, President George W. Bush identifying Iran as the “axis of evil” in 2002, and the most recent travel ban targeting Muslim countries by President Trump (of which Iran was one of the seven named countries). The result has been a stigmatization of Middle Easterners and a perception of them as a threat to American society. Increasingly, Middle Easterners have experienced discrimination based on their appearances, the way they dress (for example, hijab for women and beard for men), or by simply being Muslim—the perception being that they are crazy, barbaric, irrational, fundamentalist, and violent people.

The Iranian American community has worked hard to develop its own studies and data to properly represent and advocate for Iranian Americans in the United Sates. For example, in 2013, Professor Maboud Ansari published a study entitled “The Iranian Americans,” wherein he monitored and interviewed various generations of Iranian Americans in the United States over multiple years. In his book, Professor Ansari discussed the generational divide between first and subsequent generations of Iranian Americans. While newer generations continue to embrace their Iranian identity, they are foremost American, and reject the more traditional set of social standards held by the first generation. (See review in Peyk #151.) More recently, in 2017, Professor Neda Maghbouleh published her empirically-based study, entitled “The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race.” Professor Maghbouleh addressed head-on the identity dilemma faced by Iranian Americans who are at once technically classified as “white” by the federal government but seen as “not white enough” by mainstream society. (See review in Peyk #179.) Her conclusion is that in everyday life—at schools, in airports, in their neighborhoods, and at their workplaces—Iranian Americans are not treated as white and often experience intolerance and hate for being of Iranian descent.

Despite some progress, Iranian Americans remain an understudied group, especially in the social sciences. Whether this is because social scientists consider Iranian Americans to be “Honorable Whites” based on their light skin tone, high education, and socio-economic status or due to a general lack of interest, such research is important to address subjects such as racial discrimination, political inclusion, mental health, cultural shock, queerness, religious segregation, and more. And it is especially significant in how Iranian Americans are identified in the census.

The census helps determine how approximately $800 billion of federal funds will be allocated and the number of seats each state receives in the U.S. House of Representatives. These funds are apportioned to Medicaid, Medicare, food stamps, Section 8 housing, Pell Grants, our schools, other public buildings, roads, transportation, protection services, and community programs, among others. Census data is also used by some private companies to determine where they invest and which customers to target. Additionally, being given the “white” label puts Iranian Americans at a disadvantage when applying to universities and companies that use census information for their diversity and inclusion programs. As a remedy to making Iranian Americans and others suffering the same disconnect with being identified as “white,” some have suggested using the University of California’s SWANA category which has been successfully implemented for almost a decade. SWANA stands for “Southwest Asian/North African,” which includes those from the Middle East (but because the term “Middle East” has colonial and Orientalist origins, it has been disfavored).

For now, Iranian Americans will have to make-do with the census questionnaire as it stands. Representatives of the 2020 census are working hard this year to include all communities in San Diego County. Many Iranian Americans have a sense of distrust with the government gathering information about their racial identity, particularly after the travel ban. However, it is vital to remember that census records are protected by federal law, namely Title 13 of the U.S. Code. This law ensures the confidentiality of the information gathered and prevents use of the data to identify individuals. Additionally, the United States Supreme Court has shown a willingness to protect the privacy rights of individuals by recently rejecting the Trump administration’s attempt to add a citizenship question to the questionnaire. If the government really wanted to target the Iranian American community, it has multiple other ways of doing so than violating federal law by misappropriating census data. But if Iranian Americans do not stand up and be counted, they have a lot more to lose.

Sources:

Why Does the Census Matter, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/why-does-census-matter

Census FAQ, https://www.prb.org/u-s-2020-census-faq/

Checking White, Feeling Brown: Iranian-American Racial Ambiguity in Relation to Whiteness and Blackness by Lily Yasmin Mojdehi Bard College,

https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1294&context=senproj_s2019

Are Arabs and Iranians white? Census says yes, but many disagree,

https://www.latimes.com/projects/la-me-census-middle-east-north-africa-race/

Shaghayegh Hanson is an attorney working in San Diego. She is a member of the Advisory Board of the Persian Cultural Center of San Diego (PCC).

Lily Mojdehi is an Iranian American woman from San Diego who grew up dancing at the PCC. Majoring in sociology, she recently graduated from Bard College in New York and now works as a Middle Eastern outreach coordinator for Breaking Down Barriers, a county-funded program aiming to reduce the stigma of mental health through education and prevention programs. Contact: lilymojdehi@gmail.com