A Dogon Figure from Mali: Bridge to the Spirit World

Ladan Akbarnia, Curator of South Asian and Islamic Art, The San Diego Museum of Art

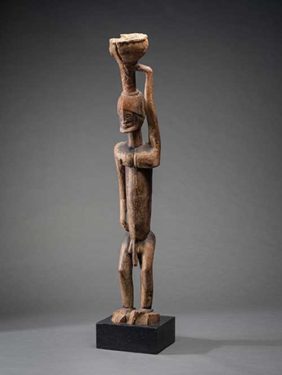

In 2019, The San Diego Museum of Art acquired a carved wooden sculpture made by the Dogon peoples in what is now Mali. It represents an androgynous male figure raising an object above his head. A gift of the late Valerie Franklin, a prominent California-based collector of African and Oceanic Art, this work forms the focus of a single-object exhibition, A Dogon Figure from Mali: Bridge to the Spirit World, on view through January 9, 2022. In the absence of a curator specializing in African art, I was honored to collaborate on this project with Dr. Denise Rogers, Professor of Art History at San Diego Mesa College, whose interest in this subject, along with the support of the Museum’s African and Pacific Arts Council (APAC) and the acquisition itself, inspired the show.

The Dogon people live mainly in the Bandiagara escarpment or central plateau region of Mali, alongside lofty cliffs running parallel to the Niger River. Located east of the Malian capital of Bamako, the area is known as Pays Dogon, or Dogon country. Migrating here around the fifteenth century for protection against potential invasions, the Dogon have maintained their heritage, religious traditions, and diverse languages over time. Yet Dogon culture also embodies the syncretism of coexistence with and conversion to other faiths, such as Christianity and Islam, the predominant religion of Mali.

The Dogon are known for their complex cosmology, architecture, and elaborate masked performances and figural sculptures. Masks and sculptures like the SDMA figure are made by male blacksmiths born into a special class and distinguished by special powers according to Dogon myths. The Dogon foundation story describes one of the nommo, or eight sacred primordial ancestors of humankind, as a blacksmith stealing fire from Amma, the supreme deity and creator, to bring to Earth; this, in turn, resulted in the creation of all natural materials and life forms. Blacksmiths are revered for their power to use and transform earth, fire, and water. Their expertise in these materials enables them to produce everyday as well as ritual objects, and to oversee ritual ceremonies.

When used for sacrifice, Dogon sculptures are known as dege, or protective figures, and serve multiple functions as representatives, intermediaries, and altars. Dege have been reported to represent sacred and immortal ancestors or deceased family members. Dogon figures may also represent the people using them to pray to Amma or to invoke spiritual guidance. When activated by the life force of the plants or animals sacrificed to them, dege become intermediaries for communication between the living and Amma. This life force transfers from the figures to the being invoked as well as to the person performing the sacrifice. When they have fulfilled their purpose, dege must be discarded or hidden until discovered by descendants, usually after the original owner’s death. At this point, the figures are no longer imbued with ritual power, but may represent the deceased.

Although the identity of the SDMA figure remains unconfirmed, the patterning of his body scarification recalls geometric patterns in scars adorning male and female Dogon sculptures. Raised arms are believed to channel prayer through vertical lines of communication to Amma, but the vessel has not been securely identified. While it resembles Dogon drums with bulging hemispheres, most Dogon sculptures representing musicians are shown playing their instruments. Other Dogon figures hold stools or containers over their heads, but those differ in shape. Shown in action, these works distinguish Dogon from other African art, where figures appear sitting or standing.

Collecting Dogon

The history of collecting Dogon material is intertwined with that of colonialism and ethnography, beginning with expeditions led by French anthropologist Marcel Griaule (1898–1956). Studied and collected by Europeans and Americans in the last century more extensively than any other culture on the African continent, Dogon material culture is associated with the founding of modern ethnography and an important aspect of African studies. Yet the differing interpretations of these works, particularly regarding Dogon myths and cosmology, also reflect the biases of those who study them. Both in and out of their original context, these objects carry complex meanings associated not only with their origins and functions, but also with the people who engage them—whether to revere, exploit, collect, or admire them.

Standing figure holding object above head. Dogon peoples; Mali, Bandiagara escarpment, 19th–early 20th century; carved wood. The San Diego Museum of Art, Gift of Valerie Franklin, 2019.27. © The San Diego Museum of Art