An Immigration Story: A Painful Decision

Reza Khabazian

Leaving your homeland and residing in another – with a totally new culture, language and set of laws and regulations – is very challenging and requires a lot of adaptation that, in most cases, is also very frustrating.

But, looking back at those challenges many years later makes some of them look funny, some amazing, and some, of course, sad.

The truth is, no matter how we feel about them, the challenges are, for sure, part of the history of immigration that needs to be documented for use by our grandchildren or simply by historians to picture the hardship that first generation Iranians had to go through to meet those challenges.

The main purpose of this column is to encourage our readers to start telling their stories so we can present a diverse documentary. The first of this series–“How I Met A Dime”–was published in the May-June 2021 issue of Peyk. This is the fourth part of Mr. Khabazian’s story.

Working part time as a maintenance person in a local motel was fun but, at the same time, $2.10/hour was not nearly enough to support a family of three.

The fun part was meeting people—some happy campers enjoying their weekend getaway, some dry and serious business people whose faces revealed how bored they were while spending their time in a motel, sleeping in a bed that could tell a number of sad, ugly, or fun stories if only it could talk. Even though meeting various guests with a variety of attitudes was, and still is, very interesting to me, financial obligations made me look for another job with higher pay.

Benefitting from my friend Saeed’s advice to look at the classified section, I found employment as a night janitor in a movie theater which paid $4/hour, but it was located in Corpus Christi, almost 40 miles away from Kingsville where I went to school to get my master’s degree. The obstacle was that this job had to be done by two people and that’s when my wife became my coworker. The union automatically brought $8/hour to my family’s pocket; we worked 35 hours a week from 11 p.m. to sometimes 5 a.m., seven days a week!

Aamrika!, you got yourself two new janitors. We love you!

Aamrika!, you got yourself two new janitors. We love you!

Working at the movie theater for almost one year was, as one can imagine, full of some scary and some funny happenings that I won’t get into now—I need to conclude my immigration story soon to give you, our readers, a chance to start writing your own experiences for all of us.

My scholastic achievements at college made me very happy but, unfortunately, the happiness was soon overshadowed by news from my homeland in the form of two huge bombshells. The first: the revolution succeeded in its goal and the Shah’s regime collapsed suddenly. Immediately, the environment at the college changed; the Iranian students were full of joy and their exuberant sounds filled every corner of the campus. But for me, being raised in a very religious family—in which even playing chess or listening to the radio were considered huge sins—the news came with a big question mark: how could a religious regime handle the needs of the people in the twentieth century?

I spent most of my free time at home glued to a short-wave radio listening to the news coming directly from my homeland. It was not encouraging. From the first week of their victory, the revolutionaries lined up almost all the old regime’s influential persons in front of their firing squad, which was located not in a military base or any prison yard, but on the rooftop of a high school where the leader of the revolution, a holy man, was residing. Almost all military generals and ministers were executed after appearing for a few minutes in front of the revolutionary tribunal. Then the leaders of other religious minorities, including an 89-year-old uncle of my wife, influential business people, and members of the political opposition groups got a taste of the revolution, followed by homosexuals and any person whom the new government considered any kind of threat to its existence. The sounds of their rifles—starting from the first week of their success—have never been silenced in my mind, even after the passing of more than forty years.

Hearing the news from my homeland that almost all my wife’s family got out of the country via illegal border crossings put me in a very sad position. On the one hand, the love of my country, its rich culture, and my friends and relatives were all pulling me in one direction; but the political condition that the country was rapidly going toward pulled me in another direction. A painful decision had to be made that kept me awake night after night.

“How can I leave my own family behind? How can I not travel through the land that I love and get mesmerized by its virgin sceneries? How can I not visit the streets that I grew up in, the classmates and friends that I have such loud and memorable memories with? How can I sacrifice the future of my marriage, the future of my only child, if I return? How can I support my family if I stay?”

After long talks with my wife over and over, finally the time came to make that painful decision.

It was not too long after the news of the revolution that the Kingsville campus was the scene of fighting between students—those totally in favor of the new regime and those totally against it. Some of the students who belonged to the Moslem student organizations quit their studies and rushed home to help the new regime, while almost all students against the actions of the new regime scratched their heads in awe!!

A few months later, the second bombshell exploded.

The American embassy was invaded by the religious mobs and all U.S. embassy personnel were taken hostage.

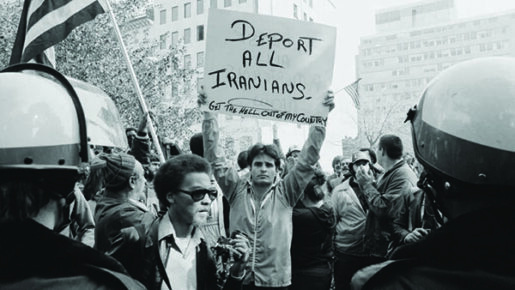

This event not only changed the life of all Iranians inside the country, but profoundly affected the environment in America and American attitudes toward all Iranians living in the U.S. Harsh treatment toward Iranian students became daily news, especially in southern states like Texas where we were living at the time. We endured the heartbreak of people throwing eggs at our cars, looking at us in anger, cussing at us when we walked on campus or in public, and preventing their kids from playing with ours. Suddenly we were in a situation in which we had nowhere to go—not back to the country in which we were born and not to the country that we were planning to make our next home!

“What am I supposed to do? I am responsible for the wellbeing of my only child. I am the one who forced my wife and son to join me to pursue my dream. Now, they are not welcome at home or here. As hard as it can be, the time to make a painful decision is approaching fast.”

The Hostage Crisis changed Americans’ perceptions of all Iranians inside and outside Iran. Not too long before, we represented a rich and glamorous culture and then suddenly we were all referred to as terrorists!

A huge demonstration against Iranian students was organized by American students to take place on campus. On that day, we were sitting in class with Dr. Bailey, who was also my advisor. As his lecture ended, without specifically mentioning the words “Iranian students,’’ he looked directly in our eyes and asked, while pointing at us: “You, you, you, and you… come to see me in my office.”

“What does he want to talk with us about,” I thought, “ask us to drop his course and terminate our studies? Hope not.”

When all of us got to his office, Dr. Bailey asked one of us to close the door. My heart was pounding vigorously. I could see the feeling of anxiety on the faces of all others in the room. When the door was shut, Dr. Bailey started to talk in a very low and comforting voice:

“Fellows! I know what kind of situation you all are in. I sympathize with you all. But I want to ask you all to minimize your appearance on campus for a few days or weeks. Just come to your classes and go back to your dorms or houses. We Americans have a very short memory. Culturally, we are trained to forget and move forward. That is perhaps the reason for our social advancement. In a few days or—at maximum—weeks, everything is going to go back to normal. All you guys need to do is to be patient and keep a low profile. By the way, my wife and I would like to invite you and your families to come to our house for dinner this Friday. We are going to eat, laugh, and dance. We all need that.”

I could easily feel the happy energy that overtook all of us after what he said.

Friday night at Dr. Bailey’s home was nothing but great food, memorable hospitality, laughter, and dancing. We even tried to teach him how to dance to the music of “Baba Karam.”

On our way home, I looked at my wife and said:

“We must not forget that this is America, not what we see these days at the campus or in public.”

Then came the moment to make the painful decision—changing our status as an Iranian Student Family to an Iranian American Immigrant Family. My wife and I both cried all the way to our house. The sad feeling has never left me alone!