An Interview with Cyrus Copeland, The author of

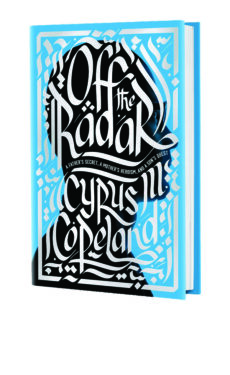

Off the Radar: A Father’s Secret, a Mother’s Heroism, and a Son’s Quest*

by Shaghayegh Hanson

For many years now, I have been keeping my eyes open for books written by Iranians living in the diaspora created since the Islamic Revolution in Iran. Somehow, Off the Radar, by Cyrus Copeland, slipped by me when it was released in 2015, off my radar until this year. This book is a powerful memoir, both riveting and beautifully written. Its focus goes beyond the events that forced Cyrus’ American father and Iranian mother to escape Iran with Cyrus and his sister in the wake of the revolution; it carries forward to Cyrus’ discovery of old, boxed documents after his father’s death that presented a mystery: was his father a CIA agent after all, as the new Islamic regime had claimed and put him on trial for? Had his father really lived a double life under all their noses, while maintaining his innocence? Cyrus’ quest for the answer is what makes this story so engrossing, imbuing it with all the page-turning urgency of a spy novel while, at the same time, pausing to connect the reader with the historical and cultural backdrop that makes the adventure uniquely Iranian and American. The Library Journal fittingly described the book as a “brilliant, touching tale of espionage, discovering family, and balancing cultures.”

I reached out to Cyrus recently to tell him how much I enjoyed the book and to thank him. His response was warm and gracious. Before I knew it, we were chatting away like kindred spirits and I was asking him if I could interview him for Peyk. I am thrilled that he agreed and that you will get to meet him, too.

SH: Your father, Max, was a native Oklahoman who deeply loved Iran. How did that happen?

CC: Marrying a daughter of Iran and visiting the country––how could you not love Iran? As your readers know, it’s a wondrously beautiful country with an unmatched ethos for hospitality. My mom and dad met on the first day of their arrival in Washington, DC, to pursue their studies, when my dad––quite the dandy––approached her in the hotel dining room and inquired if she always enjoyed the luxury of a late breakfast? That set the stage for their international love story and it inevitably took them back to Iran.

SH: Your mother, Shahin, went to England by herself at the age of 17. That was quite daring and progressive for an Iranian girl in the 1950s. Were her parents supportive of the move? How did things go?

CC: My mom was the youngest woman to leave Iran unchaperoned, but she had an insatiable love of the English language. Her parents recognized this and gave it full reign. And so she decamped for London after high school and worked as both a model and an announcer for the BBC, translating Shakespeare into Farsi for BBC Persia. She often spoke of living in London after the war, the rations, but the thing that shines brightest in memory? Her love of Shakespeare. To this day she still quotes Macbeth soliloquies. And working as a model in the Fifties gave her not only an appreciation for style and beauty––it also funded her education.

SH: Your family was still in Tehran at the beginning of the hostage crisis and then your father suddenly disappeared. Later he was tried for being a CIA spy. Talk us through those days.

CC: My father had been invited to Iran by the Shah––he was an educator and helped spearhead a curriculum for Pahlavi University in the Sixties. By the time the revolution caught fire, he had been hired by Westinghouse to shut down their operations in Iran. They had done a huge business with the Iranian Air Force and sold them very sensitive radar equipment. Long story short, some of the radar equipment which rightfully belonged to the Iranian Air Force was repatriated back to the States, and my father–– being the last man on the ground––was held accountable. Hence the title, Off the Radar. He was the first American put on trial for espionage in Iran, but his trial and much else about his life was incognito.

SH: Your mother came to his rescue, didn’t she?

CC: She did! My mom is what Iranians call a real “sheer zan”––a lioness. She had no training in Quranic law, but when my father was brought up on charges of espionage, she studied the Quran intensively for weeks and ended up representing my father before the tribunals. My mom was the very first female attorney in the Islamic republic. Think about that: A female lawyer in an Islamic country using the Quran to defend her husband who is quite possibly a spy. You can’t make this stuff up!

SH: Eventually your mom brought you and your sister to America, where there was a lot of anti-Iranian sentiment in the air. How did that affect you and your sister as children? Did you feel any blowback at school?

CC: Blowback––interesting turn of phrase, that. It originated with the CIA’s first interference in Iran in 1953. I didn’t feel much blowback at school. The kids were mostly gracious and welcoming. I felt it everywhere else though, an undercurrent of hatred and fear that survives to this day. You see it in how Iran is portrayed in the media and movies and on television—as an angry, irrational, and aggressive country. In truth, Iran is the most misunderstood country on the world stage. Despite crippling sanctions, its people are reliably and deeply hospitable. In that regard, movies like Argo and Not Without My Daughter, TV shows like Homeland, and even news coverage have perpetuated a big lie. And so, as every Iranian-American will attest, growing up between two such contradictory cultures driven by misperception and propaganda has been a challenge—but a welcome one.

SH: How so?

CC: I think we hyphenated kids hold a powerful bit of treasure. We live at the vanguard of possibility—it’s we who hold the contradictions on either end of our cultural identities. That hyphen between Iranian-Americans? It’s where the interesting work of stitching together two conflicting cultures begins. There are no Iranian ambassadors in Washington right now. But we are all ambassadors representing our homeland. And when I go back to Iran, I take my responsibility as an American very seriously––I try to be honest and open-hearted and bring the best part of my American self forward. In the absence of diplomatic dialogue, we are all cultural diplomats.

SH: Now, at some point your father passes away and you find a box of old documents that sets you off on a mission to discover more about your father’s life. What was in that box?

CC: That box! It followed us Copelands through four suburban homes over several decades to the dusty corner of a library, where I eventually found and opened it. The most interesting thing I found was a file labelled “Max’s Radar Affair” which held the frayed documents of a long forgotten “international incident” beginning with my father’s arrest and culminating with his trial. There was an article in the Tehran Times. A few letters. A packing list. It was the rediscovery of that long-buried file in my family life that led to my quest. Were the charges against my father true? Had he been a spy all this time?

SH: Against everyone’s advice, you went back to Iran. I found this part of your book very moving. Tell us about Beheshte Gom Shode.

CC: By that point in the narrative, I had come to discover all I would about my father–– I returned to Iran because I needed to go back. My father had taken us to a valley outside of Shiraz when I was a kid. He was always showing us gorgeous geographies off the beaten path. I recall that day as the best of my young life, romping through a vast expanse of beauty with my sister, leaping across streams, in a valley populated by young trees that had turned autumn gold. Before he died, I asked my father to draw me a map so I could make my way back to the valley, but I lost that map. And so decades later when a driver tells me about this place outside of Shiraz that sounded like my valley, known as The Lost Paradise, a shiver went down my spine. My father had shown us how to go out into the world in search of beauty and adventure, and more than any place that valley represented his searching heart and spirit. And so forty years later, I set out to find it.

SH: In Shiraz, you visit the shrine of Shah Cheragh, where you have an intensely spiritual experience. As a young boy, prior to the revolution, you became quite devout at some point, praying five times a day voluntarily. But by the time you visited Shah Cheragh, as a man, your relationship with Islam was, for want of a better word, complicated. What happened there and how do you feel about Islam (or religion in general) these days?

CC: It’s very difficult to put the numinous into words. I’m a Moslem and very hungry spiritually. I love the spirit of Islam but being a private and often solitary fellow, I struggle with the communal aspects of my religion. But at Shah Cheragh, I had an epiphany about how standing apart means being apart––and isn’t that the whole point of mystical pursuit, being one with everything? I found myself praying in a pool of light, between a mullah and a boy who was roughly the same age I was when my social fears about religion set in. And I knew this was a God-constructed moment.

SH: There is one thing that happens during your time in Iran which I found slightly bizarre and yet quite poignant. You attend an “Overeaters Anonymous” meeting where no one talks about food, and no one is actually overweight. Your take from it is: “In America people lie about their addictions to avoid facing their feelings. Here people declare false addictions to broadcast them.” Can you expand on this?

CC: Iran and America aren’t nearly as contradictory as they appear. We all wanna know and be known by each other. I’m not an addict but I know this: The Twelve Steps are a very effective way to share intimate truths in a trusted environment. Let me leave it at that.

SH: After all your travels and investigations, it seems you discovered things you hadn’t necessarily set out to find, while what you were looking for remained a tad elusive. Is that fair to say?

CC: I found out what I set out to find, and yes, there were many surprises along the path. Funny and profound things happen when you chart a course for the truth. When I set out to write Off The Radar, I was guided by a single question: had my father been a spy? But the narrative that followed was much richer and more soul-nourishing than anything I could have imagined.

SH: You describe yourself as being “do-rageh,” having two different veins carrying American and Iranian bloodlines. You have written, “I would come to understand that I am the by-product of the two most ethnocentric cultures on the face of the earth.” Can you expand on that? My children are also the product of both bloodlines, as I suspect are many children of our readers, so I am particularly interested in hearing how that has influenced your sense of identity.

CC: Being an Iranian-American is like being a child of divorce. You watch your motherland and fatherland demonize each other. Your mom calls your dad the Great Satan. He calls her the Axis of Evil. The divorce is epic and it’s happening on the world stage and its drawn out over 40 years. And you’re a kid caught between two warring parents. You’re scarred and you’re wise and the rift between your parents has knocked you around for a few decades and it’s also deepened you. But here’s what all children of divorce know: You never stop hoping your parents will get back together.

SH: Thank you so much for giving us your time, Cyrus. I hope you’ll keep writing because you do it so beautifully, perhaps a gift from your Persian side?!

CC: Ghabelli nadareh!

________________________________

*Available for purchase at: https://www.amazon.com/Off-Radar-Fathers-Mothers-Heroism/dp/0399158502