The Rise and Decline of Persian Hip Hop

By Vahid Jahandari

The earliest incidents of Persian language hip hop style singing and sonic integration of such phenomenon into trends of Iranian popular music occurred in the early 1990s by Tehrangeles musicians. Musicians in Iran, including those who later immigrated away, have continued the genre since the early 2000s, reacting to influences and circumstances around them. But, government crackdown and the pursuit of superficial aims has brought decay to this once substantial genre.

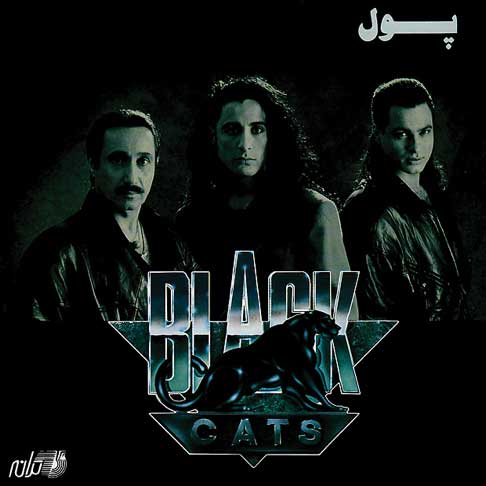

1960s-1990s: Black Cats

Shahbal Shabpareh, the founder and primary leader of the band Black Cats, rapped briefly in a series of uplifting songs on three subsequent studio albums released over the course of almost a decade, featuring the singer Pyruz before changing the group’s artistic direction.

The band’s strategy—working with artists who seemed promising, had a suitable music background, a certain charm and charisma in the eyes of fellow Iranians, and the potential for reaching the title “celebrity”—was in place since its formation in Tehran in the 1960s, when the group primarily performed covers and rearrangements by acclaimed American and British bands, such as The Beatles, introducing Farhad Mehrad and Ebrahim Hamedi among many others, including Shahbal’s very own brother, Shahram.

After a decade of silence following the Iranian revolution, Black Cats’ appearance on the LA scene was a refreshing start to a new age, making highly influential productions that inspired the birth of many fusion ensembles with futuristic impressions and engaged the audience at a level never seen before, inside and outside the country.

“Rango Reng,” “Jeannie,” and “Pool” are instances of such pieces, with groundbreaking music videos, well-received by the young and old, of all generations, from all walks of life. These songs were multifaceted in terms of musical structure and form, had a long storytelling narrative, and incorporated a variety of cultural appropriations that included visual aspects—from Native America to East Asia to the Arab world—in a comical manner that facilitated the entertaining nightclub nature of the band since its initiation, archaeologically known as “Cabaret,” a theatrical and dramatic multimedia performance.

The use of rapping was also a form of exoticism that Black Cats insisted on to amaze and attract listeners’ aural perception further and invite ears to explore a world full of wonder, encountering the unknown and inaccessible—principles that commercially successful records in North America outlined as the latest fashion aimed at the leading pioneers in the field.

Though the initial aspiration for launching Black Cats was as an English-language rock & jazz fusion band, Shahbal expanded the stylistic spectrum staged in the States through the use of bilingualism—primarily focusing on the Persian language—and by reconciling cultures, utilizing a collage of many attainable archetypes, albeit haphazardly. Varied costume designs, for example, were a direct reaction to the most dominant tendencies in the global music landscape.

With the popularity of VHS and cassette tapes in 1990s Iran, despite being officially banned by the government, a pool of productions from the American entertainment industry became available in the country. A major figure the youth found extremely fascinating was the extraordinary music and electric dance of Michael Jackson. The band members who joined Black Cats after Pyruz frequently exhibited behaviors mimicking MJ’s way of self-expression, whether that was singing, dressing, gestures, and/or choreography.

MJ’s “Black Or White,” which received the first ever Billboard Music Award for No. 1 World Single in 1991, was released only one year before Black Cats’ first album in the States came out. The imitation of specific aesthetics in what Shahbal redesigned from that influence can be noticeably observed during this era. MJ’s collaboration with hip hop legend Notorious B.I.G. and many other iconic artists in the 1990s appeared to inspire innovative producers to combine various literary expressions in a single track.

1990s: Shahram Azar

Another distinctive musician of the Tehrangeles golden period—Shahram Azar (known as Sandy), who was born in Abadan—composed and produced songs within five consecutive albums from 1994 to 1998 that integrated elements from the region he grew up in with the popular music context of the time. The song “Talagh” (Divorce) combines Bandari style (the title drawn from the characteristics of traditional music in the port city of Bandar Abbas) with the use of a synthesizer, replicating the sound of Persian bagpipes, responding between the verses’ gaps with drum beats—a direct reference to the common approach of performing rhythms of Darbuka, a hand percussion regularly practiced in southern Iran around the Persian Gulf region where it is considered a cultural symbol. “Talagh” dives into the issues that expatriated Iranian couples fall into after migrating abroad, encountering a modern and rather different society, far from the ideologies that shaped their understanding of a “good life” in their own country.

“Bikari” (Unemployment), “Matalak” (Sarcasm), and “Cobra” (an Iranian girl name) are other notable instances where Sandy critically discussed challenges the Persian community faced, particularly the ones youth struggle with while being alien in other nations: in search of Westernizing their identity, unhappy from their racial/societal descent, and not feeling like making any fulfilling movement toward or away from a void ideation of “the self” they could hypothetically impersonate, ultimately facing a deadlock. The cycle continues.

Early 2000s: Hichkas, Tataloo, Pishro, and Tohi

In the early 2000s, a group of enthusiasts in their early 20s who found themselves very interested in pursuing hip hop—Soroush Lashkari (known as Hichkas), Amir Tataloo, Reza Pishro, and Hossein Tohi—had gatherings where they practiced and developed freestyle rap in the capital city, Tehran. These close associates then pushed the limits to become completely independent creative forces of underground music in Iran, coining the first generation of Persian hip hop in its purest form, all of them superior to this date. With the exception of Hichkas, who remained thoroughly authentic to his socioeconomic status and therefore represented the living of deprived people, the other three portrayed otherwise.

In their first official song, “Boro Az Pishe Man” (Get Away From Me), Tataloo, Pishro, and Tohi presented ‘021’ (the dialing code for the Tehran Province), appearing in uptown neighborhoods with murals filled with English letters, playing basketball, and depicting “the wealthy boys” without much concern in life except love affairs, a theme that continued with tone variations pretty much throughout their musical careers. Later on, each of them declared in interviews to have grown up in low-income families and having had to do labor work before rising to fame.

Hichkas’ Jangale Asfalt (The Asphalt Jungle) was released in 2006 and considered the first original Persian hip hop album, with a massive and ever-lasting impact; the songs were played everywhere, causing a surge among the youth chasing hip hop. The first track, “intro,” starts with a lyrical poem of Hafez (a 13th century mystic poet), declaimed by the singer, and followed by an instrumental duo of Ney and Tombak that gradually transforms into heavy and distorted drumbeats and electronic-type soundscape. Jangale Asfalt is highly experimental and progressive in terms of utilizing traditional Persian instruments and materials into confrontation of juxtaposing genres.

In “Ekhtelaf” (Discord), the most popular track on the album, Hichkas gives an overview of the obstacles to making it through life that the Tehran population faces every day—in the chorus section, asking God to wake up and hear him out. Hichkas emigrated to London shortly after releasing the single “Ye Rooze Khoob Miad” (A Good Day Will Come), a response to the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests. While the creative output of Hichkas substantially decreased after leaving the homeland, the rise of Tataloo prevailed in the underground scene.

Zire Hamkaf (Below Surface), Tataloo’s first studio album in 2011, included many top hits and, from there, he continued producing songs that lead to him being recognized as the most-viewed personality in Iran. The track “Ye Chizi Begoo” (Say Something) shares the most intimate communications, unspoken from “the one” drowned in love with a partner who no longer wants the relationship. This type of lyricism in Persian music, with explicit and vivid monologues, took the audience to headspaces they had not experienced and yet somehow resonated with them—songs that expressed the collective rumination and suffering lovers may deal with after breakups in premarital romantic partnerships.

The poetics of Tatality (associated with Tataloo’s approach to rhetoric) concentrated on the areas that, in an Islamic-governed republic, were perpetuated as “out of custom” to the overall perception advertised through the regime’s platforms and propaganda. After years of struggle for licensing his works through Iran’s official media broadcasting, strategizing the dream of concerts and touring, but none reached, Tataloo had to escape disciplinary actions, immigrating to Turkey, continuing with a more compelling wave of involvement in music and lifestyle, not having found his ambitions come true in a politically-segregated country called home.

A Decline, In Progress

The fall of Persian hip hop began due to a crackdown on artists in Iran and when records produced outside the country began following the hollow trends of “woke hip hop” or “socially conscious rap.” Numerous singles by Tataloo in the past few years have followed these vacuous trends.

“Shokret” is a relatively recent collaborative track by Tataloo, Tohi, and Pishro. The recording’s cover is designed with characteristics of neon-noir digital illustration, squeezing in imagery from flying saucers and extraterrestrials to astrological symbols and contemporary architecture—erroneously signifying the psychedelic spirituality movement—while the actual music conveys no tangible relationship to these elements, from the instrumental component to the lyrics that are so to speak “dropping wisdom.”

“Baby Oonam Dooste Mane” came out only two weeks after “Shokret” and showcased the next level of desecration and demoralization. These works are replete with obscene and profane language, filled with dirty, sexually explicit hints, vulgar phrases, and cussing to evoke strong reactions, seemingly in an attempt to increase the likelihood of rising through the streaming charts and downloading websites like RadioJavan.

The ramification of these shortcomings in rapping and discourteous voices can be witnessed in all other hip hop subgenres, specifically Gangsta rap; the popular Iranian band Zedbazi is an example. This series of productions usually tends to confuse fluency in oratory skills over substance and urgent expression over integrity. Yaser Bakhtiari (known as Yas) has built up the majority of his portfolio with this formula: saying nothing in many words while using extravagant flowery language and posing like a pretentious royal in casual outfit—habitually wearing a Faravahar pendant as one way of delivering it.

As despairing and irrelevant as Persian hip hop can get, anger, resentment, disappointment, and discomfort from a monotonous routine are the max listeners might take away from comprehending the songs. The geopolitical roots of Iran’s economic crisis and inflation, rising prices across the country on a daily basis amid international isolation, have disheartened all the people.

Vahid Jahandari is a musician and composer. He is currently pursuing his doctorate in music composition.