Leaving your homeland and residing in another—with a totally new culture, language, and set of laws and regulations—is very challenging and requires a lot of adaptation that, in most cases, is also very frustrating.

But, looking back at those challenges many years later makes some of them look funny, some amazing, and some, of course, sad. The truth is, no matter how we feel about them, the challenges are, for sure, part of the history of immigration that needs to be documented for use by our grandchildren or simply by historians to picture the hardship that first-generation Iranians had to go through to meet those challenges.

Peyk kicked off this column in 2021 with Reza Khabazian’s story, with a goal to encourage our readers to start telling their stories so we can present a diverse documentary. Now that Mr. Khabazian has published his story, it is time for new stories and new voices. This is the first part of Kourosh Taghavi story.

The immigration story of every person is important enough to be worth documenting. The more diversified the background of these persons and families is revealed, the more colorful the picture is portrayed for the reason behind their immigration.

For this issue, we start covering the immigration story of yet another member of our community who left Iran at a young age. Mr. Kourosh Taghavi is a local artist, a musician who has been devoted not only to the art of music, but also as an active member of our cultural community who devotes his time and energy to promote the art and culture of Iran.

Reza Khabazian (RK): I would like to thank you, Mr. Taghavi, for accepting our invitation to go through the story behind your immigration. We at Peyk certainly hope that your story, along with the stories of other members of our community, can be beneficial to our younger generations on realizing the hardship that their parents had to go through so they can have a better life and more prosperous future. To get started, as you left Iran at a very young age, please take us through the environment of the household that you were growing up in.

Kourosh Taghavi (KT): First, let me thank Peyk for giving me the opportunity to share my story with your readers. Second, to answer your question, I must take you to the time when I was only 10 years old. I grew up in a household in which not only my parents but also my older sister and older brother were political activists. My father was self-employed in agriculture and my mother was a private school teacher who later became a school director. Some years later, my father donated a piece of land which enabled my mother and a few other ladies to build an orphanage in our hometown, the city of Gorgan.

RK: So they were not only political activists, but also social activists!

KT: That’s correct. They were socially active to the last days of their lives. They even created an NGO [non-governmental organization] to run the orphanage and several people came to help their cause. But I should mention that my parents were involved with politics at early ages and witnessed the 1953 coup d’état which put both of them in jail for a short while. When I was 10 years old, both my sister and my brother were college students and both were involved with political activities.

RK: Can I conclude that you were raised in a very serious family?

KT: Not at all. We had so many fun moments, laughter, jokes, took several trips together, and at the same time we were totally aware of what is going on in the country. Let me give you an example; one of the most important places at our house was a huge library. Books from all aspects of life could be found in our library. From politics to philosophy, from art to social issues, and so on. Therefore, the chance of being informed was given to me. On the other side of the coin, when I was growing up, the country was going through some important turmoil. I was only 11 years old when the armed resistance against the regime happened, known as Siahkal. Then, in 1975 with the trial of Golsorkhi that was broadcasted live, I heard vividly the term “Partisan” (Chereek) for the first time from my older brother and thought to myself that maybe one day I could be one, too.

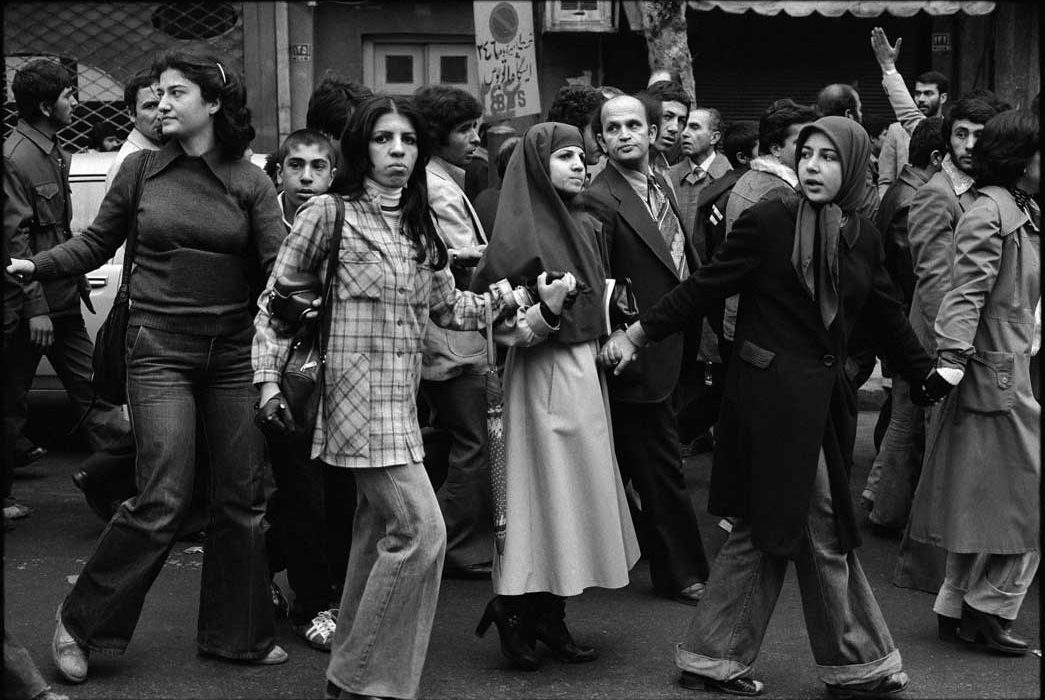

RK: How do you remember the years leading to the 1979 revolution?

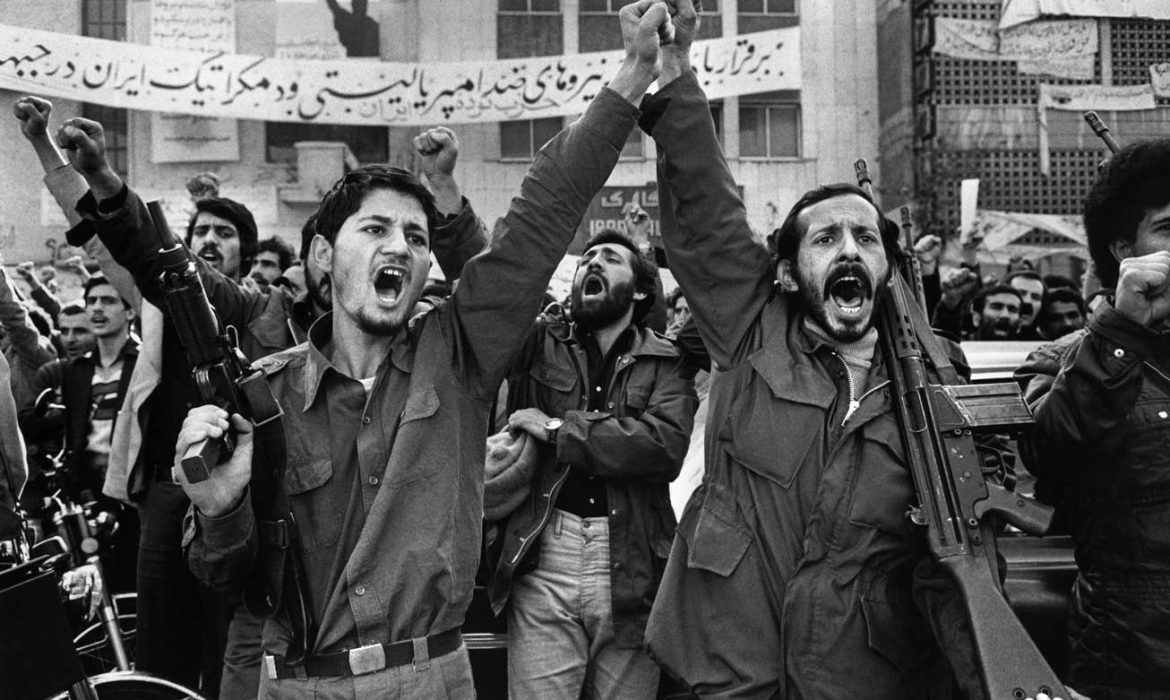

KT: During that era, I should say, I was 11, 12 years old, finishing my primary school years, when the country became unstable and the news of uprising was spreading every day. When the 1979 revolution happened, I was a freshman in high school. All those years I was very worried about my brother, mainly because of his involvement in anti-regime protests. My feeling was that something was going to change when various political parties emerged and became very active after many years of living in the shadows.

RK: Did you get actively involved with any one of the parties?

KT: As soon as I heard the name of “Chereeks of Fadaian Khalgh,” I joined them. Not only me, but almost every youngster at my age and a little older found a party that they eagerly joined. Students who had a religious background joined Mojahedin Khalgh, people having nationalistic viewpoints joined the “National Front,” and so on. You need to consider that the environment in the entire country became political. Demonstrations and strikes became a daily discussion among the public. Now, you can imagine what was going on in my own family.

RK: What were the leaders of your political party encouraging you to do besides participate in demonstrations?

KT: They were emphasizing reading. Therefore, many books started to circulate among us which overall helped me to create a vision for myself. Also, apart from reading, political and philosophical discussions became a norm. Overall, I regarded myself as a leftist with anti-imperialist views, especially after the hostage crisis.

RK: As a person with leftist ideology, what were your thoughts about the people forming the new Islamic government?

KT: We regarded them as a bunch of liberals who also had anti-progressive ideas.

RK: How did you regard Khomeini?

KT: We regarded him as the leader of the revolution, a very charismatic leader. Beyond that, we did not like his stand on democratic values, especially his religious ideology. As a matter of fact, the party that I felt close to voted NO to his referendum that only had one question on it: Islamic Republic, yes or no.

RK: I am sure you, like most Iranians at that time, were very happy to see the old regime collapse, hoping for better days ahead. When did you realize that what prevailed is not what you were hoping for?

KT: Not too long after the revolution. Let me give you an example: right before the revolution, an association was formed in our town called “Association of Teachers of Gorgan.” People from all walks of life joined the association. In one of the meetings, after people from my party finished talking about our agenda, a person who was a member of Hezbollah went to the podium and regarded our platform with such animosity that I could clearly see what a heavy obstacle we were facing. Another example shocked me that happened when we were taking an exam that was required to enter the universities. After they collected the tests, they asked us to continue sitting. Then, they gave us a blank piece of paper and asked us to draw a map of our own community, marking the exact location of our house and the homes of everybody we knew who was anti-government. A few friends that happened to sit close to me looked at each other and decided not to obey. I remember the instructor said to all of us that “if you don’t follow the order, your test won’t be even looked at.” I joined my other friends and walked out of the room, sending my dream of being a college student out the door.

RK: Going back to the series of turmoil that Iran went through right after the revolution was the war that broke up between Iran and Iraq. What were your thoughts about that?

KT: The war united Iranians to fight for their country. People from left of left to the hard-core Hezbollah all volunteered to participate. Saving the country was in the minds and hearts of everybody.

But, unfortunately, the clash between left and right survived underneath the society, something that still exists to this day. I remember that I was in my last year of high school when a friend of mine left school to join the army who were fighting at the border between Iran and Iraq. He was a member of our party. As he was fighting against the enemy, a revolutionary court in Gorgan gave him an absentee death sentence. That was how the animosity was rooted deeply. Capture, imprisonment, and receiving harsh sentences like execution became the destiny for anybody belonging to leftist parties. The fear of being captured made me spend less time in our hometown and travel from place to place, making my parents very worried about my future, especially when going to university to continue my education was not an option anymore. One day, when I got home, my parents and my older brother and sister were sitting around the table waiting for me to get home. I could easily see the worry on their faces. My mother asked me to join them at the table, looked directly in my eyes, and without any pause said:

“We all are very worried about you living your life like this. You are not allowed to go to college under these circumstances. On top of that, we are sure sooner or later they are going to come after you. If that happens, God knows what is going to happen to you. Therefore, we all have talked it over carefully and decided to send you out of the country. It is going to be an illegal border crossing. As hard as it might be, unfortunately, it is our only choice.”

RK: What was your reaction?

KT: I paused and looked at the faces of my family, one by one. All of them were staring at me, waiting for my response. I felt a heavy silence in the room that I had to break by saying:

“I agree with you.”

That short sentence started my path to become an immigrant.

____________________________________________________

Kourosh’s immigration story will be continued in our next issue.