Organized Sound Processing and Constructive Body Movement

By Vahid Jahandari

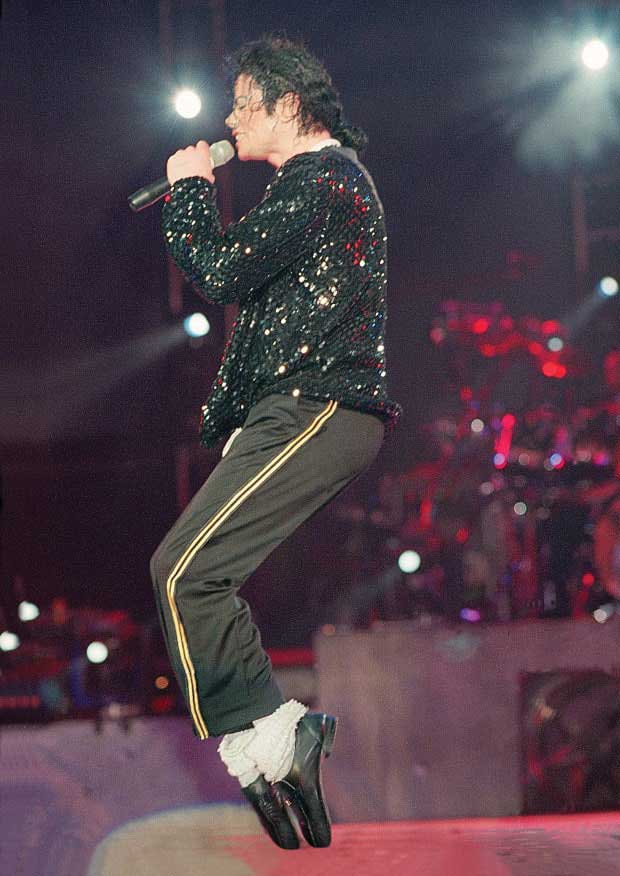

As an interdisciplinary artist, musician, and scholar, I have had the privilege of collaborating with choreographers and dancers across a wide spectrum. Additionally, during my formative years, I was captivated by the extraordinary performance of Michael Jackson. In my adult years, I continued to study his creative process, particularly his complex approach to sound processing and body movement. That said, my sustained immersion in these disciplines has inspired me to write this article, delving into the transformative potential of music and dance in improving mental and physical health, as well as social interactions.

Exploring Methods of Auricular Wellness

Emerging findings indicate that liberated unchained frequencies—especially those exteriorized from musical instruments and projective elements like headphones or speakers—can directly aid in psychophysiological rehabilitation. They may, in turn, facilitate alleviating energy-point blockages—interlocking all vessels, organs, and muscles—within the circulatory system. These imbalances within the nerves are primarily caused due to immediate anxiety and manifestations of PTSD. (1)

These discoveries illuminate the construction of skeletal (bones) and flesh (tissues) by navigating sonic procedures to revitalize the entire anatomy and ultimately enhance physiological strength. The approach integrates concentrated sound processing into the auditory perception—through the ears. Simultaneously, the brain orchestrates a ramified response to function according to the aim and expertise of the auditor in realizing and computing receptive signals, and as such, set and setting plays an inevitable role. The aim and expertise of the auditor are interconnected. The more educated a client is about music, the more fruitful the results of examination, exercise, and drilling of aural particles into the headspace. (2)

On the Nature of Vocalized Organisms

Our brains continuously record every single event since birth, and the idea of the subconscious mind and the conscious mind are about the same concerning the ultimate human conduct. The subconscious is designed and obligated to channel all figurative materials and rewire a limited portion of its collection into the conscious, including but not limited to hearing, smelling, and seeing, from the individual’s evolutionary environmental encounters (externalized data) as well as involuntarily visions (dreams, flashbacks, and other pre-diagnosed or unidentified phenomenon) to a location commonly referenced as memory, which is the ongoing mass accumulation of matters. The conscious mind transmutes the filtered view of identity to the senses of comprehensive awareness and free will for making proactive choices. However, reactive behaviors that include vocables—coming out of our mouths—are very intended disruptive acts of the subconscious for reasons primarily understood as survival mechanisms and defensive management, inherited by all living beings. (3)

For instance, the vocalization of foxes when feeling any threat to their surroundings varies, depending on their confrontation, including whining and yelping to initiate certain attention from their own group, and larger Canidae family. They also employ barking and growling as tolerated shielding of their observed atmospheric horizon or warning purposes. (4)

Tuning Inward for Outward Observance

Music listening practice should be recognized as a form of meditation. Regardless of the depth or duration of this stimulation, it can induce a contemplative state. This holds true irrespective of the genre and whether the individuals are selective producers (deliberate choices) or an outer and ungoverned medium is radiating it toward them. This issue is very critical because exposure to vocal music with sophisticatedly hindered use of vocabulary, maliciously situated for its addictive or indoctrinated properties, has the potential to make a detrimental impact on cognitive faculties. Therefore, it is imperative to be mindful of your choices and timing, as these components directly influence aspects of suspended reasoning and emotion. (5)

Being exposed to songs that hint at racism, sexism, and/or fascism can desensitize a person to people of other races, religions, and regional backgrounds, as well as to their commitment to social justice and gender equality, albeit gradually. This deterioration can affect a person’s ethics, principles, and virtues. Such instances may extend beyond mere implications and result in even more destructive consequences, undermining shared values within broader society, the nation, and global concerns related to the safety and security of the planet and its inclusive and generative force of existence. (6)

Television wields immense power in (re)shuffling perspectives. When it comes to programming global music and dance—for instance, consider the montage-like strategies and operations of Michael Jackson, which is centralized around a cosmopolitan landscape—television can serve as a potent catalyst for promoting cultural awareness and fostering diversity, ultimately advancing internationalism. (7) It is imperative to acknowledge that television possesses the potential to serve broad educational purposes aligned with overarching ideological objectives. Media, in its various forms, can adeptly strike a balance between entertainment and edification. For a more in-depth exploration of this sphere, I highly recommend perusing Dr. Sandra Minto’s recently published book, Rechoreographing Learning: Dance as a Means to Bridge the Mind-Body Gap in Education. (8)

Spatiality via Sonified Momentum

In the realm of anthropological research on music and dance, an extensive inquiry encompasses the spatial and ethical dimensions through which sound permeates and impacts mind and body. The given or chosen auditive treatment shapes our lives, carving our behaviors and interactions into infinite contexts. Dance serves to forge intimate connections among individuals and strengthen group solidarity. This account suggests that embodied sonification is inherently sociocultural activism, irrespective of whether it involves systematically designated “musicians” or “dancers.” (9)

While I acknowledge that music and dance may not strictly fit into any predefined geographical categories, I resist the notion of treating dance as merely an aspect of music or vice versa. I advocate for a nuanced examination of these seemingly distinct creative domains, even though I have found them to coexist and be complementary. I wish to emphasize the mutual influence of sound and movement on the essence of mankind. Recognizing the fluid boundaries between music and dance, I advocate for a broad understanding of both, highlighting their interconnected significance in promoting holistic health. It is crucial to focus on how individuals perceive and utilize sound and movement. Through this lens, we can unravel the intricate connections between the material world, identities or spirits, and bodies that are correlated through these two means of contact. (10)

Mirror Neurons for Cooperative Compassion

The therapeutic potential of dance and music, particularly within the context of Sound & Movement therapy, focuses on the practice of mirroring, which is considered an invaluable exercise to enhance mutual understanding and empathy. Mirroring involves imitation by the client, including the emotions and intentions that are mirrored by the targeted entity. The scientific field that examines this area is called “mirror neuron.” (11)

I do not believe in isolating music and dance, but in exploring them within the framework of sound and movement, which then enables us to realize the potency of arts as a scientific field for optimizing people’s well-being and fostering their flourishment. Sound and movement are fundamental to the nature of the universe and deeply woven into existence. All of the ever-known biological organisms and incarnated species are somehow involved in this flow. (12)

Reviving Lives with Rhythmic Therapies

Parkinson’s disease, a neurodegenerative disorder affecting millions worldwide, primarily manifests as motor symptoms, but also involves other autonomic and sensory nervous system issues. The depletion of dopamine affects voluntary motor processes, leading to a variety of clinical symptoms. Medication treatments have limitations. Alternative therapies, such as dance and music-based therapies, have gained attention for their positive impact on quality of life and motor control. Music is not only a resource for equalizing emotions, but also serves as a guide for initiating pre-meditated and spontaneous movements. (13)

Sensory Worlds and Shared Anthropology

In specific cultural traditions, anthropologists propose that sound and movement play a crucial role in shaping who we become within our communities. Vocal sounds and bodily movements act as tools for self-fashioning, nurturing distinct social identities. Ethnographers who explore sound and movement find themselves fully immersed in a sensory world. This immersion leads to a unique form of social interaction, blurring the lines between the researcher and the subject. Researchers become active participants, using their bodies as essential research tools. This shared intimacy parallels Jean Rouch’s concept of “shared anthropology,” emphasizing the connection between bodies, space, and personal development in relation to others. (14)

In “How Dance Observation Affects Meter Perception,” the authors explore the relationship between visual stimuli, dance movements, and auditory perception, focusing on how watching dance affects sound perception. (15) The article delves into the connection between visual and auditory information, highlighting studies demonstrating how watching performers’ body movements can alter various aspects of sound perception, from music expressiveness to rhythm structure. The article also discusses previous research indicating that human body movement plays a crucial role in rhythm perception, impacting the way individuals interpret rhythm and synchronize with it.

Furthermore, the article investigates the impact of viewing dance on meter perception, particularly in relation to music. It discusses how dance patterns often align with the beat and meter of accompanying music, with different dance components reflecting distinct metrical levels. The study aims to explore whether watching dance can elicit a sense of meter and how this affects sound perception. Additionally, the article touches on the dynamic attending models of rhythm perception, which suggests that meter guides attention and enhances perceptual processing of beats on higher metrical levels.

To assess the influence of visual stimuli on sound perception, the article presents experiments involving participants responding to sound targets while watching dance videos, static visual stimuli, and a control condition with no accompanying video. By comparing these conditions, the study aims to shed light on the ways in which visual stimuli, such as dance movements, shape auditory perception, particularly in the context of meter perception. This research holds promise in the pursuit of effective, efficient, and safe wellness increase.

Conclusive Statements

The synergy of organized sound processing and constructive body movement has the potential to improve our well-being and reshape societal dynamics—numerous research about the topic has unveiled their profound impact on mental and physical health, identity, and social connections. It’s vital to be discerning in our choices, avoiding contents that might erode values and unity. Breaking down the divisions between music and dance allows us to appreciate their intertwined nature. Embracing this synergy unlocks insights into the nature of our humanity and the unparalleled potential to elevate our overall vitality to unprecedented heights.

References:

(1) Dissanayake, Ellen. “Ancestral Human Mother–Infant Interaction Was an Adaptation That Gave Rise to Music and Dance,” The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 44: e68–e68 (2021).

(2) Poikonen, Hanna, Petri Toiviainen, and Mari Tervaniemi. “Naturalistic Music and Dance: Cortical Phase Synchrony in Musicians and Dancers,” PLOS One 13 (4): e0196065 (2018).

(3) Handel, Steven N. “Designing for Insects and People: Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” Ecological Restoration 40 (2): 102 (2022).

(4) Hagen, Edward H. “The Biological Roots of Music and Dance: Extending the Credible Signaling Hypothesis to Predator Deterrence,” Human Nature (Hawthorne, N.Y.) 33 (3): 261–79 (2022).

(5) Woolhouse, Matthew Harold, and Rosemary Lai. “Traces Across the Body: The Influence of Music-Dance Synchrony on the Observation of Dance,” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: 965–965 (2014).

(6) Nekola, Anna E. “Teaching Americans to Be International Citizens: World Music and Dance on Television’s Omnibus,” Journal of the Society for American Music 13 (3): 305–37 (2019).

(7) Survey MJ’s auditory-based visual exhibitions in songs like “Black or White,” “Remember the Time,” “They Don’t Care About Us,” and “Heal the World,” among many others.

(8) Minton, S. C. Rechoreographing Learning: Dance as a Way to Bridge the Mind-Body Divide in Education. Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK (2023).

(9) Yu, Jiashuo, Junfu Pu, Ying Cheng, Rui Feng, and Ying Shan. “Learning Music-Dance Representations through Explicit-Implicit Rhythm Synchronization,” IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 1–10 (2023).

(10) Njaradi, Dunja.“Trance, Music and Dance – Old topics and new interdisciplinary dialogues,” Etnoantropolos̆ki problemi 13 (4): 987–1005 (2018).

(11) Marmeleira, J., & Duarte Santos, G. “Do Not Neglect the Body and Action: The Emergence of Embodiment Approaches to Understanding Human Development,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, 126(3), 410–445 (2019).

(12) Dalziell, Anastasia H., Richard A. Peters, Andrew Cockburn, Alexandra D. Dorland, Alex C. Maisey, and Robert D. Magrath. “Dance Choreography Is Coordinated with Song Repertoire in a Complex Avian Display,” Current Biology 23 (12): 1132–35 (2013).

(13) Jola, Corinne, Moa Sundstrom, and Julia McLeod. “Benefits of Dance for Parkinson’s: The Music, the Moves, and the Company,” PLOS One (2022)

(14) Chrysagis, Evangelos, and Pana Karampampas. Collaborative Intimacies in Music and Dance: Anthropologies of Sound and Movement. New York: Berghahn Books (2017).

(15) Lee, Kyung Myun, Karen Chan Barrett, Yeonhwa Kim, Yeoeun Lim, and Kyogu Lee. “Dance and Music in ‘Gangnam Style’: How Dance Observation Affects Meter Perception,” PLOS One (2015).