An Immigration Story:

Trinidad

A short story by Ali Sadr – Part 1

Leaving your homeland and residing in another—with a totally new culture, language, and set of laws and regulations—is very challenging and requires a lot of adaptation that, in most cases, is also very frustrating. But, looking back at those challenges many years later makes some of them look funny, some amazing, and some, of course, sad. The truth is, no matter how we feel about them, the challenges are, for sure, part of the history of immigration that needs to be documented for use by our grandchildren or simply by historians to picture the hardship that first-generation Iranians had to go through to meet those challenges.

Peyk kicked off this column in 2021 with Reza Khabazian’s story, with a goal to encourage our readers to start telling their stories so we can present a diverse documentary.

In this issue, we reprint a short story by Ali Sadr that was published several years ago. Among the immigration stories that we are presenting in this column, we saw a relevance to revisit this story that is based on actual events. The story is about Ali Sadr coming to the U.S. to continue his education in 1976. Due to the length of the story, we had to break it into two parts. Here is the first part:

“Trinidad!” “Trinidad!” The bus driver was tapping on my shoulder. “Didn’t you want to get off in Trinidad?” He was yelling at me. I couldn’t remember where I was. It took me a few seconds to get myself together. I jumped out of my seat. “Oh man, what a deep sleep!” the driver exclaimed.

“Trinidad!” “Trinidad!” The bus driver was tapping on my shoulder. “Didn’t you want to get off in Trinidad?” He was yelling at me. I couldn’t remember where I was. It took me a few seconds to get myself together. I jumped out of my seat. “Oh man, what a deep sleep!” the driver exclaimed.

I looked at my watch but couldn’t see a thing. The clock at the front of the bus showed 11 o’clock. It was pitch dark outside. A dim light inside the bus showed the other passengers were mostly asleep. I followed the driver out of the bus. He asked if I had any luggage. I said yes. He then opened the baggage compartment and I showed him my suitcase. He pulled it out, mumbled goodnight, jumped onto the bus, and took off. Two couples got off with me, too. Two taxi cabs were waiting in front of the bus station. The couples each took one and left.

The bus station consisted of a small shack with a couple of benches and a counter. An older gentleman, apparently the manager, was standing in front of the shack. He suddenly turned around, turned off the light, locked the door, and disappeared behind the building in the dark. A light was dangling from a wire above the door, swinging in the wind and playing with the shadows. I looked around. I was the only one standing. There was not a soul around. A cold breeze was blowing. I was standing in front of the shack not knowing where to go. Apparently, I slept for a few hours on the bus.

When I got on in Denver the bus was half full. It was going to El Paso, Texas, but it would stop at Trinidad, the most southern town in Colorado. No one was sitting next to me on the bus, so I had the whole seat to myself. I thought to myself, “Great, maybe now I can get some sleep.” I couldn’t remember the last time I was able to get some decent sleep. Was it three or four nights ago?

It was two nights before I departed from Tehran that I got some sleep. The night before I left was total chaos. Everyone was there at my parents’ house. My brothers, sisters, and uncles with their families, they were all there. Kids were running around. I hadn’t even packed my suitcase. It was after midnight when they left and promised to be at the airport in the morning to send me away. I was really anxious and somewhat scared. But I was fine with that. How bad could it be?

I was supposed to go to Trinidad, Colorado, for four months to attend English classes before going to Syracuse University for graduate school. Why Trinidad? you may well ask. Simple, it was the only ESL school that responded to my application quickly enough to enable me to get my passport and visa on time and get out of Iran.

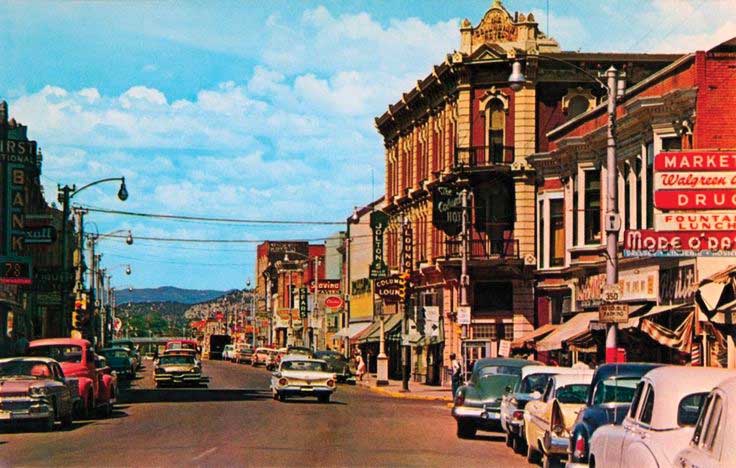

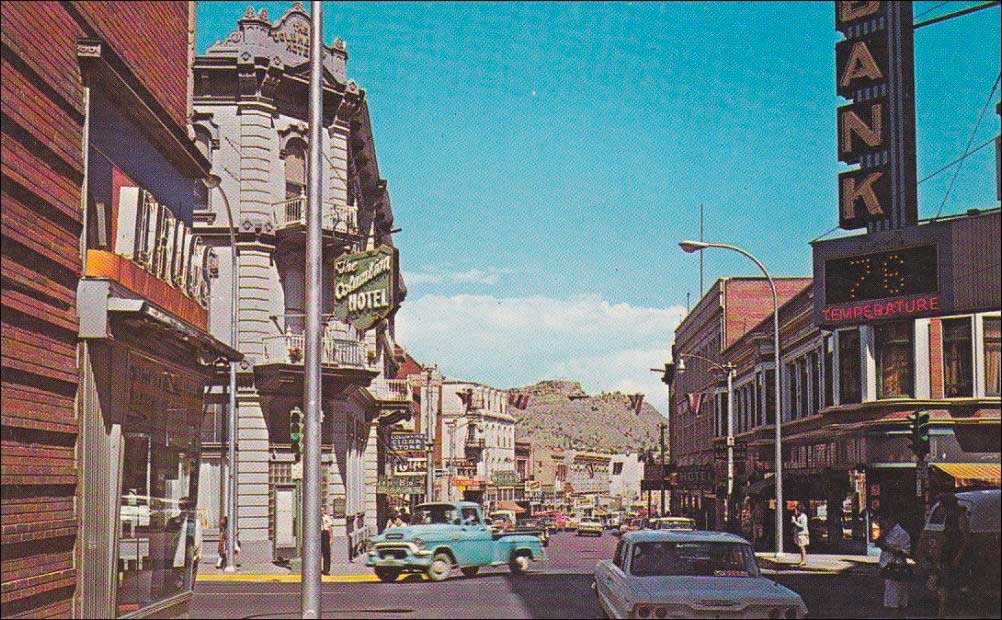

And now, here I was in Trinidad, at a deserted intersection with a single set of traffic lights dangling in the middle of it, changing colors for no one; no cars, no pedestrians, nobody… nothing, just a cold breeze! It was pretty cold for late April. The town was ghost-like. After what had happened to me in New York and Denver, I started panicking again! I wish I had asked the station manager for directions. I knew I had to find the college dormitory. Standing there was useless. I turned onto the street to my left carrying my large red suitcase.

As soon as I turned I saw a big sign for 7/11. Yes! Something familiar, I knew what this was. I had seen it in the movies. I walked faster, dragging my red suitcase behind me, holding on tight to my briefcase! My money was still in my boots. It was safer there. I rushed across the street, not having to worry about getting hit by any cars. There were two cars parked in front of the 7/11 store.

***

I had arrived at JFK airport after a lengthy flight. Everything was interesting to me—men and women with cowboy hats and boots, black people, very large uniformed workers walking around. I followed the crowd to the luggage area. Ahmad, my coworker in Tehran who had gone to school in Detroit, Michigan, and returned to Iran about a year before, had walked me through this part a few times before I left. Now I had to change my terminal and go to TWA to catch my flight to Denver. Ahmad had advised me to walk out of the terminal and take one of the shuttle buses to the other terminal. Pretty straightforward, right?

Ahmad had also warned me not to get a ride from strangers. He emphasized, “Beware of blacks.” He himself had his suitcase stolen at JFK Airport. He had explained: “I had two suitcases and a bag hanging from my neck. One of the suitcases wasn’t even mine! My aunt had asked me to take it to my cousin who lived in Detroit.” It was full of “soghati” stuff (presents)—noon barbari, pistachios, sohan, gaz, and some artifacts. He recalled the suitcases were heavy. As soon as he walked out of customs, he came face to face with a nice black gentleman with a nice afro. “He asked me if he could help. I thought he had noticed how beleaguered I was, having to carry two huge suitcases and sporting a third, hanging off my neck, and felt sorry for me. I said no thank you, I would handle it myself. He said fine. I noticed that he had a small bag too. I thought to myself, he is probably a passenger himself, just trying to help. He gave me another look and smiled. I told him okay and handed him one of my suitcases, the one with my own stuff. He said not to worry, that he would just follow me. I said I was going to the other terminal to catch a flight to Detroit. He said he was going the same way. He then started asking questions about my flight, where I was going, and stuff. I was excited to practice my English. He said he was from Detroit; at least that’s what I thought he said. We came out of the terminal to the bus stops. He said something and started walking faster. I asked him to slow down and wait for me. He kept going. Then… he disappeared! Totally! I looked around for a while and then went to the other terminal, hoping that he was waiting there for me. I had missed my flight and there was no sign of the guy. I sat on my only suitcase full of gaz and pistachios and cried like a baby. No one even bothered to ask me why. They probably thought I was homesick or something.” He warned, “Don’t trust anyone, especially blacks, and only take one suitcase!” He was still obviously bitter about the experience after so many years. I had taken his advice and only brought one suitcase with me.

Now, stranded in the middle of nowhere, I felt so depressed. I missed everyone, even Ahmad. I had believed I would be able to handle the separation. It was only going to be for a few years, to get my master’s or perhaps a PhD. Besides, I had always wanted to come to America. This was the adventure of a lifetime. On the one hand, I was excited, on the other I was scared. A world of unknowns. Would I be able to handle it? Would I be able to survive with $5,000 in America? That was all my savings, I had no other resources! Everyone was giving me advice: “Not to worry, in America you can work. America is very different from Europe. In America, there is always work for students.” And they would give examples of the people they knew that had started working right away as a waiter, parking attendant, or selling ice cream, while they were going to school.

None of these musings and worries really mattered though. I had to get out of Iran. After I graduated from Tehran University, I had six months to either continue my education somewhere or submit to mandatory military service for two years. I spent the entire six months trying to get an acceptance from a university. Two weeks before the deadline, I succeeded. I got my passport and visa within one week, and just a few days before the deadline I was on an Iran Air jumbo jet going to New York, via London.

Most of my classmates had already been serving for those six months and were getting ready to be sent to Oman to fight and save the Kingdom against a popular rebellion in Zoffar province. This was one of the proxy wars that the Shah, the best ally of the United States, was conducting on behalf of the U.S. Since I was a year younger than most of my classmates, I had time to do something. For most of the time, it had been a discouraging process. I received several rejection letters and most schools I liked hadn’t even bothered to respond. So it was like a miracle when I finally got a letter from Syracuse University, accepting me for the fall semester. It felt great! But I had to leave before May 1, only a couple of weeks away. I managed to get into an ESL, a language school in Trinidad, Colorado, to improve my English for four months. Until then, I thought Trinidad was a country in the Caribbean! This was a small town in the south of the state of Colorado.

This was my first trip abroad. So much excitement and so many unknowns. I knew no one in the United States. What an adventure for a twenty-one year old! Was I able to handle it? What if? What if I couldn’t? I would then have to go back! What a disaster!

I had gone to see my boss just one week before my departure. He wanted to see me. He didn’t know I was leaving the country. Before I said anything, he started in again advising me, telling me I needed to cool off my head. He said when he was my age, he was hot-headed, too, but he soon found out that it was just childish stuff and that if you cared about society you should work through the system. He continued, “You have to join The Party, otherwise, I have to fire you.” He said, “There is only you and Mahmoudi who haven’t joined the ‘Rastakhiz Party.’ Everyone else has joined.” I knew he was right. To get paid everyone had to sign up. This was the Shah’s newly founded political party and he had decreed that all Iranians were to join The Party, or leave the country! My boss continued, “They will find out. I can no longer protect you. You remind me of myself when I was younger. It’s no use. You can’t fight the system.” I calmly said I knew, and I didn’t want to cause him any trouble, so I was quitting. He jumped out of his chair and asked me, whispering, “Tell me you are going abroad! Right?” I said I might be and would see what happens. He was obviously excited and relieved that I wasn’t his problem anymore. He called accounting to cut me a check with [a little bonus]. Now I had all that money and my savings left after paying for my flight. I had almost five thousand dollars with me.

***

I entered the 7/11. With the sound of the bell, the clerk turned towards me. It was nice and warm inside. I could smell the food. Suddenly I felt hungry. The clerk was talking to two customers, I think in Spanish. I waited in front of the electric rollers, rolling greasy hot dogs up and down. After a minute or so he turned toward me and asked if he could help me. I think that’s what he said. The other customers stared at me. I said I wanted to go to the college. He completely understood me and smiled. He asked me if I was hungry and wanted to eat anything. I said no, I just wanted to go to college. While he was walking toward the door, he asked me to follow him. He said, “Everything is closed until tomorrow.” We walked out. He pointed towards the opposite street and said, “Go up that road, you will see the college on both sides of the road, good night,” and went back in. I started walking into the dark street, pulling my suitcase behind me.

***

At JFK, after I got my passport and papers stamped, I retrieved my suitcase and briefcase and walked out into the U.S. The first thing that grabbed my attention was the size of the people. I felt so small. A big lady at the desk looked at my ticket and told me I had to go to the TWA terminal to catch my connection to Denver. I had over two hours. I felt a little relieved—“So far not bad!” As soon as I walked out of customs, I came face to face with hundreds of people holding signs with names in different languages or perhaps just waiting to see their friends or relatives. I didn’t expect anyone, so I just waded through and out of that crowd. I put my suitcase down to catch a breath and figure out where to go. Suddenly, a nice-looking gentleman with a nice dark blue suit came to me and asked to see my papers. Yes, he was white and clean-cut. I thought he must be somebody from the airport. I gave him my ticket—not the passport, I was smarter than that! He started explaining slowly but loudly that I had to go to the TWA terminal. I said I knew and had to take a bus in front of the terminal. He said I might miss my flight. He continued that he was going there and could give me a ride to get there on time. He didn’t grab my suitcase, just asked me to follow him. He had a huge black car. I didn’t know at the time that this car was called a “limousine.” He opened the trunk and helped me put the suitcase in. Then he asked me to sit in the front. He was very polite. He sat behind the wheel and drove between the cars and buses. He was quiet. I wanted to talk to him, but my English was worn out, too; besides, I didn’t have a good feeling about this, already.

End of Part 1. The second part will be in the next issue of Peyk.