By Ali Sahebalzamani

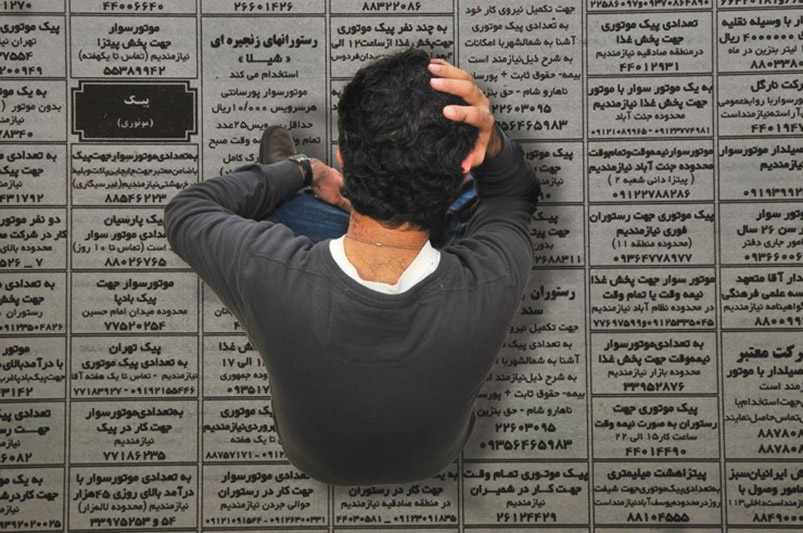

Mere weeks before the recent chain of riots and unrests, I left the country of my birth and childhood, carrying with me the weight of self-imposed exile, knowing that it may be years until I see many of the closest people to my heart. The bitterness of that knowledge, however, was overshadowed by the joy of escaping that toxic environment. Living in Iran these past few years has not been easy; the shadow of absolute economic collapse looms heavy. All people, except for a very select few, descend further into poverty at an hourly rate, regardless of the kind of work they do or the amount thereof. The bottom of the middle class has dropped off and the lower echelons are rapidly falling into abject poverty. It is a normal thing, for example, to see a civil engineer driving a cab, and even then barely scraping by. The sight of dirty urchins selling pocket napkins and chewing gum on the street has become so normal that now, having moved here to America, my eyes still have not adjusted to their absence. As a result of this state of hopeless destitution, a pall of despair has fallen over the country.

Living in Iran these past few years has not been easy; the shadow of absolute economic collapse looms heavy.

The most glaring result of such all-encompassing helplessness is frustration, which itself almost always shows itself in society’s behavioral pattern as Rage. Street fights, often with fatal results, have become a regular part of the urban landscape. Strangers on the street stare each other down, as if daring the other to throw the first punch. The police are even worse as they are, of course, armed. Among the less aggressive members of society, such as the intellectual and artistic minorities, this anger always turns into self-destructive behavior; drug-abuse and self-harm being the most common forms. Last year, my closest friend tried to take his own life, though unsuccessfully. Afterwards, when I enquired as to the reason of his suicidal decision, he provided only a casual shrug and a few terse words: “I felt like nothing was ever going to get better.”

In this poisonous atmosphere, the common people have altogether forgotten about principles such as decency and honorable conduct—as if the blatant corruption and thievery of the system permits them to behave in whatever beastly way they please. The only thing on their minds is to somehow “win,” no matter who might be on the losing side or the circumstances of their triumph; the accountant who embezzles money from his employer is considered “clever,” the retailer who gets away with overcharging is a “shrewd businessman,” and the one who cheats on his or her partner is the “winner” of the relationship. All of this amounts to a feeling of constant threat from every quarter, making me, and people like me, increasingly reluctant to participate in society. I hid behind my solitude so to speak. The viscosity of my isolation in Iran is beyond what I can describe using my current meager writing skills.

…in America, one thing is certain and that is the fact that all citizens are expected to behave well.

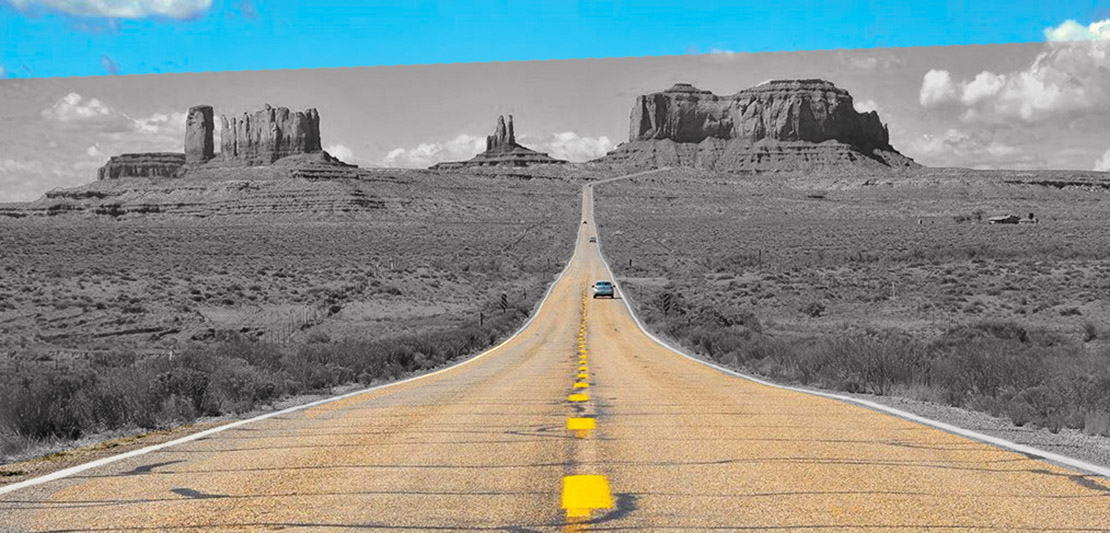

To me, the most striking quality of American society is how fundamentally moral it is. The very first culture shock that came to me was when I saw that everyone is essentially trusted by their peers. All members of society are presumed to be honest, decent, law-abiding citizens unless proven otherwise. In Iran, such a notion would be considered at best naiveté and at worst simple-mindedness. Even through all the division and uncertainty that is currently rampant in America, one thing is certain and that is the fact that all citizens are expected to behave well. That, to me, is beyond wonderful; all people, no matter how deeply they disagree with one another, will participate in society in a civilized manner. Another American quality that struck me was that in order for one person to win, no one else had to lose. The success of each individual is not necessarily entwined with the downfall of another; this state of being pushes all members of society to strive towards their own betterment, in which ever way they desire. For me, that is writing. Those long months of solitude in Iran weren’t completely wasted, as that almost monastic way of life forced me to become intimately familiar with myself. In the absence of human interaction, writing stories became my main passion. So much so that, for the first time in my life, I was investing as much time and energy as I had in a single activity, exercising discipline I didn’t know I possessed. It was a sort of ecstatic drunkenness at first, as my father took to training me in the correct writing of Farsi. Thus, for the first time in twenty-something years of life, I knew what I wanted to be. I began to retain stories like a sponge; I decided to keep my eyes and ears open and to maintain a high degree of sensitivity towards each second as it passes me by. And those around me noticed; they started coming to me with amazing stories: their childhood in the rural parts of Iran, how they met their spouse, or their memories from the days of the revolution. Different lives that have been miraculously lived. I listen and I remember everything obsessively. Now, this obsession is the needle of my compass, the reason for my very being, and I am certain that on the subconscious level, this is the actual reason for my emigration: to hear more stories and, hopefully, create a few of my own.

Ali Sahebalzamani is a 24-year-old psychology graduate who recently migrated to the U.S. He can be reached at aliespandar@yahoo.com.