The U.S. Healthcare System:

A Problem With an Obvious Solution

By Maz Hadaegh

Like many others who immigrated to the U.S. from Iran in the 1980s, my family’s journey was via a third country, France. Within days of arriving in Paris at the age of 7, I had the misfortune of falling face first on a cobblestone sidewalk, resulting in a badly bleeding forehead. After getting help from our tiny hotel’s concierge, the visit to a local hospital went smoothly; I was quickly examined by a nurse and doctor who sterilized my wound, applied bandages, and concluded that the situation was not very serious. I distinctly recall my mother nervously trying to figure out how to pay for the visit, but the people she asked were a little puzzled by the question. In the end, we were pleasantly surprised to learn that there would be no charge.

Fast forward five years later when my family finally made it to the U.S. Within days, my sister developed what appeared to be a bad cold which she couldn’t shake. Being brand new to the country, my parents had not yet started working and, therefore, did not yet have health insurance (which, quite frankly, is something I’m not sure they thought much about at the time). My sister had a short visit with a doctor at his office—maybe 15 minutes long, at the most. The doctor concluded that my sister was probably okay and just needed more rest, and thankfully she recovered within a few days. It did not take long, however, before my parents began receiving multiple doctor bills amounting to over $500 ($1,130 in today’s dollars), an absolute fortune for new immigrants.

This visit to the doctor had a chilling effect on our family as we all understood when you do not have health insurance, you do not go to the doctor unless it is a very serious issue. In retrospect, we were quite fortunate not to have a major illness during the years we had no insurance. Even once I obtained insurance from my employer as an adult, I was shocked at the price of health services and disappointed by “surprise bills” I would receive months after a visit, like when my wife spent a couple of hours in the ER and racked up over $10,000 in bills (fortunately, our “good” insurance policy only required us to pay $4,500 out of pocket due to our high deductible). My experience with different forms of health care systems and my experience even with “good insurance” caused me to start investigating why the U.S. health system operates in the way it does and what the potential solutions are to fix it.

The State of the U.S. Healthcare System

The United States is the only country in the developed world not to guarantee universal health care as a right. As a result, its healthcare system is an inequitable, wasteful, and expensive apparatus which leaves 29 million people completely uninsured and at least 47 million more underinsured, meaning millions who have health insurance cannot afford the exorbitant out-of-pocket expenses. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, 68,000 Americans lost their lives annually due to affordability or inadequate access to healthcare, and another 500,000 Americans declared bankruptcy each year due to their inability to pay their healthcare bills. [1] This, in the “richest” country in the world.

Even more shocking, the U.S. spends more than its international peers on healthcare and with worse health outcomes. This is the case whether we measure cost on a per capita basis ($11,000 per capita in the U.S., about twice the median of our international peers), or as a share of GDP (17% of GDP, versus our international peers who spend 11% of their GDP on healthcare on average). [2] On key health metrics including life expectancy, child mortality, and maternal mortality, the U.S. significantly lags countries of comparable income and GDP per capita. [3]

Simply put, the U.S. healthcare system is in a class of its own. And it’s not an enviable one.

The Affordable Care Act: A Stopgap Giveaway to Private Corporations

In a purported effort to “fix” the healthcare system and cover more Americans, Congress enacted the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. Commonly known as Obamacare, the new law, among other things, added regulations for minimally-allowable insurance, expanded Medicaid, and created healthcare exchanges for people to purchase insurance (using government subsidies if their income was sufficiently low).

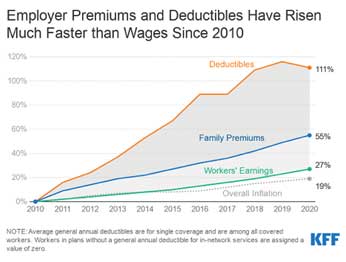

While the ACA resulted in some improvements—including a reduction of the uninsured rate among the non-elderly (from about 17.8% in 2010 to 10.9% in 2019) and elimination of health insurance companies’ ability to discriminate based on pre-existing conditions—its principal mission of making healthcare affordable failed miserably as healthcare premiums and deductibles have continued to outpace inflation and worker wages by a large margin. [4] Furthermore, even this modest step toward universal coverage came at the expense of mandating Americans who did not already have health coverage to purchase it from private insurance corporations, entities which are designed to maximize profit and have little incentive to make healthcare affordable. Although the ACA attempted to resolve major structural problems, it really has proven to be an expensive band-aid rather than a cure.

Proposed Solutions for the U.S. Healthcare System

So what can be done to improve the system? There are many proposals, but the key ones are: (1) expanding the ACA, (2) adding a public option, and (3) creating a single-payer healthcare system.

With regard to expanding the ACA, the federal government could funnel more subsidies to individuals, employers, and insurance companies to get the nation incrementally closer to universal coverage. This is probably the worst idea fiscally as taxpayers would be subsidizing private insurance companies who have proven to be miserable at controlling costs. The private insurance companies’ number one mission is to maximize profits, and an expanded ACA would essentially guarantee even more profits for them at taxpayers’ expense.

A “public option,” basically a health insurance plan offered by the federal government (potentially with government subsidies), would give consumers an alternative to the private insurers with the goal of reducing costs. The effectiveness of a public option would vary widely depending on the exact implementation. While it seems like a sound idea on the surface, in practice, the private insurance companies could undermine the public option by, for example, making their plans very attractive to healthy people and pushing the unhealthy people (e.g., older people or those with chronic conditions) to the public option. The private insurers can do this quite easily and legally by, for example, depleting their networks of oncology services, thereby driving those “costly” patients to the public option. This will inevitably cause the public insurance premiums to skyrocket over time, opening the public option up to political attack. Simply put, the public option keeps our existing multi-payer system in place and just makes it even more complex.

Another prominent proposal is single-payer healthcare in which the government is the single payer (insurer) in the system but the providers (doctors, nurses, hospitals, etc.) are all still private. The government guarantees all medically necessary care, including hospitalization, doctor visits, dental, vision, hearing, mental, reproductive, and long-term care, plus prescription drug coverage, with virtually no out-of-pocket expenses at the point of service.

Single-payer healthcare is not a new idea; it has been a policy proposal for decades in the U.S., but has recently gained grassroots popularity as “Medicare for All.” Single-payer systems already exist and have proven quite successful in many countries, including Canada, Australia, Taiwan, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The existing U.S. Medicare program is itself a single-payer system for those 65 years of age and older, and has proven to be much more effective at controlling costs in comparison with private health insurance companies (e.g., roughly 12% of premiums for privately run Medicare Advantage plans are spent on overhead, compared to just 2% in traditional Medicare programs). [5] A single-payer system promotes competition among providers for the best cost and the best service; it simply eliminates the middlemen (private insurers and their profit motives) which do not add any value when it comes to health and only serve to inflate costs (because they have to pay their executives and deliver profits to their shareholders).

Single-Payer Healthcare: Cost-Effective, Popular, Opposed By Corporate Interests

But can we afford to cover everyone under a universal single-payer system? Absolutely. Study after study after study has shown that a single-payer system would save the U.S. between 2 and 5 trillion dollars over a decade compared to our existing system, largely due to reduced administrative overhead and cost controls. [6,7,8] Hospitals and employers would no longer need to hire an army of insurance administration clerks and benefits administrators to navigate and negotiate our complex system. Further, with the government operating as the only healthcare buyer, it would exert economic pressure on healthcare providers and pharmaceutical companies that have been price gouging consumers. Finally, by having everyone insured, we can prioritize preventative care and wellness, which is much more cost effective than emergency care (which is the most expensive way to deliver care).

And a single-payer system here in the U.S. is popular; about 69% of all Americans support it according to public opinion polls. [9]

So if the problems with our healthcare system are so stark and the solution so clear (and proven), why do we continue to put up with a system that is so obviously broken? The answer is simple. It’s money and politics. Large campaign donors and corporate lobbyists have an outsized and corrupting influence on how policies are formulated. The healthcare and pharmaceutical industries spend more “influence” money (on lobbying, media misinformation, campaign contributions, etc.) than any other industry—and they don’t want a system that replaces them with a more cost-effective coverage of care. In the 2020 election cycle, the healthcare industry spent at least $600 million on lobbying activities alone. [10] Those same corporate interests also have an outsized influence on our media. As a result, the media rarely covers Medicare for All in a fair or even-handed way. While the corrupting influence of money in politics is not limited to the healthcare sphere, it is one of the most egregious examples.

Whether the U.S. moves toward a universal single-payer system will depend in large part on the battle between grassroots activists and organizers against well-funded corporate healthcare interests who wish to maintain the status quo.

https://spendmenot.com/blog/medical-bankruptcy-statistics/

https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#item-spendingcomparison_health-consumption-expenditures-per-capita-2019

https://ourworldindata.org/health-meta

https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

https://www.salon.com/2020/02/15/american-health-care-system-costs-four-times-more-than-canadas-single-payer-system/

https://jacobinmag.com/2018/12/medicare-for-all-study-peri-sanders

https://theintercept.com/2018/07/30/medicare-for-all-cost-health-care-wages/

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)33019-3/fulltext

https://thehill.com/hilltv/what-americas-thinking/494602-poll-69-percent-of-voters-support-medicare-for-all

https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/industries?cycle=2020

1 Comment

Aline Koppel May 8, 2021 at 8:16 pm

Succinct and well-presented!