An Interview with Mr. A

Leaving your homeland and residing in another—with a totally new culture, language, and set of laws and regulations—is very challenging and requires a lot of adaptation that, in most cases, is also very frustrating.

But, looking back at those challenges many years later makes some of them look funny, some amazing, and some, of course, sad. The truth is, no matter how we feel about them, the challenges are, for sure, part of the history of immigration that needs to be documented for use by our grandchildren or simply by historians to picture the hardship that first-generation Iranians had to go through to meet those challenges.

Peyk kicked off this column in 2021 with Reza Khabazian’s story, with a goal to encourage our readers to start telling their stories so we can present a diverse documentary. Now that Mr. Khabazian has published his six-part story, it is time for new stories and new voices.

It was a Sunday afternoon when I visited Mr. A, after so many years, in a government housing unit to record his immigration story. Before I begin reflecting on our conversation, it is necessary to mention that—due to the sensitive content of his immigration story, with respect to his privacy—we can not mention his last name. This interview has been edited for clarity and space considerations.

Reza Khabazian (RK): On behalf of Peyk, I would like to thank you very much for allowing this interview to take place.

Mr. A: You’re quite welcome.

RK: Let’s begin with years ago, I mean before the revolution, and ask you to give us a little background of yourself and your family.

Mr. A: (long pause) Well, I don’t know where to start?

RK: Let me ask you a more direct question: what were you and your family doing at that time, your occupations, your status?

Mr. A: Oh, we were married a few years before the revolution. I was employed by the ministry of justice and my wife was an elementary school teacher in a public school. A few years after our wedding, with the help of my uncle, who was a successful businessman, we purchased a small house in an ordinary and inexpensive part of our town.

RK: So, you both were government employees!

Mr. A: Yes.

RK: When did the idea of leaving the country emerge in your thoughts?

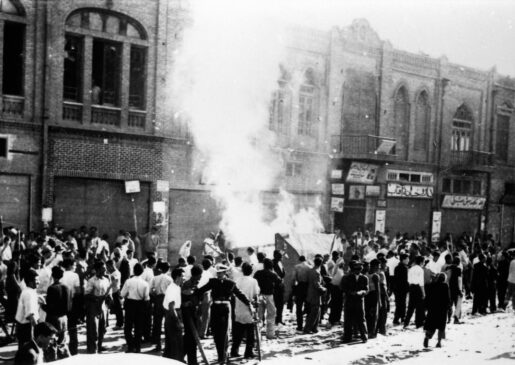

Mr. A: I think nobody likes to think of leaving his or her homeland. We were no exception, but you know, when you are a member of a religious minority, you always pray for peace and quiet in the country. If you study our recent history, any time that our country went through any social or political turmoil, the members of all religious minorities were harassed, attacked, or even killed.

RK: What do you think was the reason for that?

Mr. A: First, as you know, the prejudice against religious minorities always existed in our society. In other words, minorities have always been victimized without playing any role in creating the social or political problems. That was the reason that we were always praying for peace so we can get along with our normal life. Normally, it did not mean that everything was 100 percent pleasant—we had minor problems here and there—but, overall, the situation was manageable. Second, I think they believed we were part of the government. Why they thought that way, I don’t know.

RK: When did you realize the situation was moving in the wrong direction?

Mr. A: After a couple of uprisings in a few cities. I think it was late 1977 or early 1978 that the issue entered in our daily talks at dinner tables or at our group gatherings.

RK: In these dinner table discussions, did everybody share the same worry or not?

Mr. A: The older generations were more worried than the younger ones—they were worried that there was a chance for history to repeat itself. But, the younger generation argued that the era of such adverse actions was long gone. Based on their arguments, today’s people of Iran are more educated, more open to accept the rights of all minorities.

RK: What about you? Which side were you more leaning toward?

Mr. A: Personally, I was more in agreement with the older generation and my wife more in tune with younger ones. She was criticizing me of being too pessimistic. Unfortunately, it did not last too long that her opinion changed drastically as well as the opinion of most people in our religious group.

RK: Please tell us what happened that caused the opinion to change? (In asking this question, suddenly I felt the air in the room got too heavy. Mr. A took a long pause, kept looking at a distance, and then continued.)

Mr. A: It was almost late 1978, the entire country was on strike. The entire country was under martial law, all schools were closed, government offices were shut down, demonstrations against the government were a daily activity all over the country, news of deadly clashes between the demonstrators and the army became the subject of every conversation. Me and my wife were quietly sitting at home in that late afternoon of an autumn day, both worried about the future of the country as well as our own future when, all of a sudden, we heard a big bang on our front door. We both looked at each other in a panic. I stood up and hesitantly started to go toward the front door while asking my wife to stay in the room. The banging got louder and louder. I saw the door was pushed harshly open. Right before I got a chance to open the door, it opened by force and an angry crowd of probably 15 to 20 people rushed themselves into our front yard—some carrying picks and shovels, some carrying huge yard sticks, and one carrying a gas tank! I started to scream at them:

What the hell are you looking for?

Get lost you bastard!

You are a bastard , get out of my property, NOW!

Clear the way you Filthy (Najes), we are here to carry “Shariah” law. Come on guys, start!, he said while pointing at the crowd.

I looked at my wife watching us from the window, terrified and pale! I told her to come down and stay with me. The crowd started going to our rooms and a few minutes later some exited carrying our belongings—a radio, TV, rugs, dishes, clothes, whatever they could get their hands on.

RK: What about your neighbors? Did anyone come to help?

Mr. A: Some were watching from their windows and a couple rushed in to help. Our neighbor said, “I swear to God, Mr. A, they are not Moslem, this is not what ‘Shariah’ teaches us,” as he was trying to get us to his home for safety. He turned to one of the mob and shouted: “You must be ashamed of yourselves, hope you all burn in hell!” When we got to the alley, it was full of people, just watching.

RK: Just watching?

Mr. A: Just watching and nodding.

RK: I am so sorry to hear that. It is awful!

Mr. A: Yes, it is awful. It took only a few minutes before we saw smoke coming from our living room. The mob exited our house and rushed to burn another house and another house. In no time, smoke filled the entire alley. Immediately, I called our relatives and informed them about the incident so they could get prepared. After the mob’s departure, some other neighbors came to put the fire out. So, in just less than half an hour, we became homeless, with a house half burnt and most of our belongings gone. That was it. It did it. It made my wife change her way of thinking.

RK: Where did you stay that night?

Mr. A: At our neighbor’s home until the next day when my uncle and parents came to see us right after the martial law allowed them.

“Look at my son. Thank God you two are alive and safe,” said my uncle, while holding me in his arms, my parents were both crying. “Do not worry about the damages, I will help you to put the house in order, repair, and also replace all of your belongings that you lost. Let’s go to our house, our place is safe. We are next door to the police station.”

We had no choice but to move to my uncle’s house, hoping to have the worst behind us. Unfortunately, we did not know that this incident was just the tip of the iceberg… .

____________________________________

Mr. A’s immigration story will continue in the next issue of Peyk.