My dear friend Manuel witnessed the soul-crushing death and rape of his siblings in the early 1980s at the hands of the Salvadoran military. He was fortunate to escape to the United States, a country that was financially and militarily aiding and abetting the massacre of his people. Manuel has shared with me the story of his nightmarish journey to safety. I may have forgotten the exact details of his journey, but I will never forget how telling the story made him feel. Politicians may need a lie detector test to determine the veracity of their claims. But not refugees. Anyone who has spent time with a refugee can tell you how they feel when they access their lived trauma. Forget words, their trauma is most visible in their physiology: teary eyes, sweaty palms, tense muscles, cracked voice. Put your hands on their painfully stiff shoulders, there is your veracity. Over the years, Manuel has learned how to deepen his strength to overcome his wounds and losses.

The Salvadoran Civil War began in 1979*. Under the banner of eradicating communism, the government formed death squads and violently targeted union members and leaders, students, farmers, catechists, and Catholic monks, nuns, and any church delegation who challenged its absolute power. El Salvador is much smaller than neighboring Guatemala which had a more prolonged civil war. Compared to Guatemala, the war in El Salvador was quicker but more targeted and brutal. Between 1980 and 1983, half a million Salvadorans and Guatemalans fled military and political persecution by crossing Mexico and ultimately coming to the United States. In December 1981, the Salvadoran Army surrounded the village of El Mozote and massacred up to 1,000 innocent people, many of them women and children. Journalists who visited the site the next day recorded vomiting incessantly because of the nauseating smell of burnt human flesh. Ronald Reagan’s State Department initially denied that the massacre had even taken place, only to change its official stand when evidence of the massacre’s occurrence became overwhelmingly indisputable. Even after the massacre, Reagan called the Salvadoran government “friendly” and “democratic” and continued U.S. military aid to El Salvador.

The U.S. had recognized the rights of asylum seekers under President Jimmy Carter, who signed into law. The United States Refugee Act of 1980, whereby “the Congress declare[d] that it is the historic policy of the United States to respond to the urgent needs of persons subject to persecution in their homelands.” Yet, under Ronald Reagan, only 2 percent of all Salvadoran and 1 percent of Guatemalan asylum seekers were granted asylum in the U.S. Compare that with 30-40 percent of Polish and Afghan asylum seekers fleeing the Soviet Union, a political and ideological adversary, who were granted asylum in the United States during the same time period. The Reagan administration repeatedly lied about the conditions of Salvadorans—its lies provided a gross misrepresentation of the fact that returning home was a death sentence for people like my friend Manuel and thousands of his compatriots who fled their homelands.

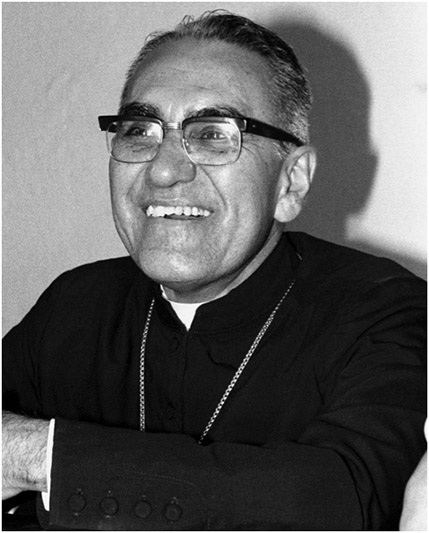

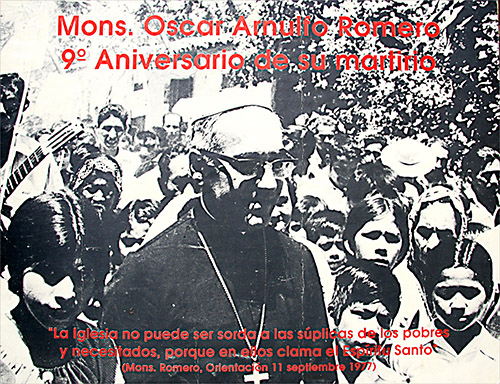

Less than one week after the 96th Congress and the Carter administration codified asylum into U.S. laws, a brave Salvadoran man spoke out against state violence in his country. Óscar Romero, the Archbishop of San Salvador, the highest cultural figure in the country, spoke the following words in his sermon on March 23, 1980, in San Salvador: “I would like to make a special appeal to men in military uniform: brothers, you are from the same people. You are killing your peasant brothers … We would like to remind the government that none of its reforms will serve any good if they are drenched in so much blood. In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people whose lamentations reach the firmament … I beg you, I plead with you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression.” In his own words: les suplico, les ruego, les ordeno en nombre de Dios: Cese la represión.

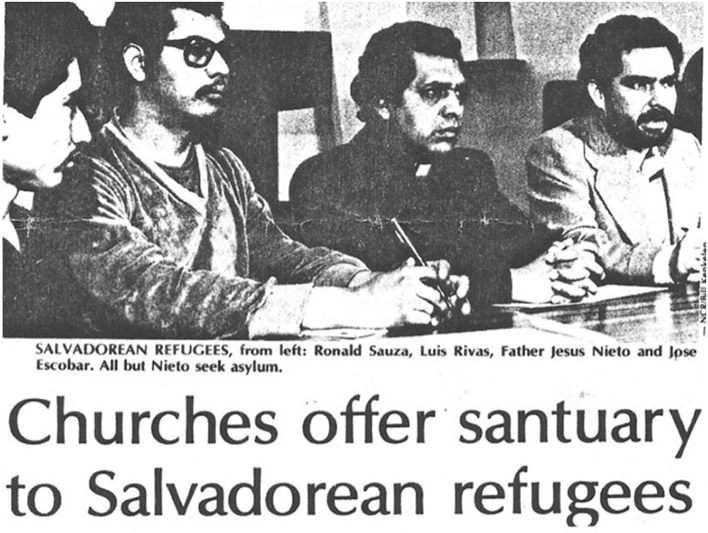

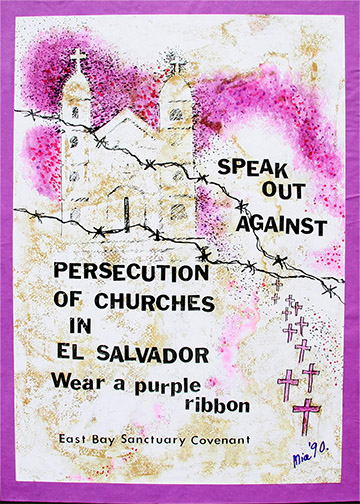

The Salvadoran military did hear his words. The next day he was gunned down during mass. But many others also heard Monseñor Romero’s words. Human rights activists and church leaders held vigils for him across Latin America and the U.S. His memory inspired many to defy the Reagan administration by helping Central American asylum seekers cross into the U.S., giving them water and shelter, and declaring their communities a “sanctuary.” John Fife, minister of the Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, and Reverend Gustav Schultz in Berkeley were such people. They helped form the Sanctuary Movement, giving legal advice and community support to thousands of asylum seekers who were wrongly denied protection from the U.S. government. The Sanctuary Movement is still alive, supporting a growing community of refugees in California and Arizona.

Fife and Schultz risked arrest and defied what they rightly perceived as inhumane and reckless practices by the Reagan administration (a man who is on tape calling African diplomats monkeys). Thanks to their activism, George H. W. Bush signed into law the Immigration Act of 1990 which gave protection to thousands of Salvadorans, a status that Manuel received before he applied for permanent residency. Also, thanks to their pioneering efforts, thousands of Guatemalan and Salvadoran have received asylum here. Salvadorans and Guatemalans form one of the most hardworking and successful communities in the U.S., contributing to our economy, arts, culture, and literature. Also in the 1990s, hundreds of LA gang members were unfortunately deported to El Salvador, a country that was in no way ready to deal with the type of U.S. organized crime that was exported to Central America, later cohering into groups like MS-13.

I was not even born when the Sanctuary Movement began. In fact, the misguided policies of the U.S. government in Central America span more than my entire lifetime. When the current occupant of the White House took his oath of his office in January 2017, I became a volunteer at the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant, an organization first formed in response to the humanitarian crisis in El Salvador and Guatemala. Few thought there would be an urgent need for it forty years later. At EBSC, I have interviewed dozens of asylum seekers with diverse profiles: gays and lesbians who had found the body of their partners in trash bags, unaccompanied minors who ran away far from home after gang members coerced them to join their criminal enterprise, women who had been gang-raped and left in a coffee field to die, and farmers who had rejected orders from narco-traffickers to plant drugs. In all their diversity, each case was a testament to the sanctity of human life in the face of cruelty and rampant criminality.

Now, we have a president who has separated families at the border in order to deter them from lawfully seeking asylum and ended Temporary Protective Status (thus threatening to deport 275,000 American-born children along with their parents to Central America). He grossly claims that “we are full” and cannot take any more refugees while reducing the number of refugees in 2020 to a historic low (18,000 to be specific, in comparison with 85,000 capped under Obama in 2016). But his worst offense is abusing using the power of his office to coerce foreign leaders to carry out his political agenda. No, I am not even talking about Ukraine for which he will likely be impeached. Trump threatened to cut aid to Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala if they did not immediately stop the coming of asylum seekers to the U.S. To appease Trump, the Mexican president cowardly utilized his army to abuse and stop innocent asylum seekers at the Mexico-Guatemala border. Now, Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala have declared themselves as “safe third countries,” meaning if any asylum seeker sets foot in their soil, by law, they will have to apply for asylum there, wait out the process, and be denied there before they can apply for asylum in the U.S. There is only one problem: those countries do not have an open and fair asylum system, a fact that U.S. federal judge Jon Tiger acknowledged in his July 24 ruling. The Trump administration has effectively ended asylum for Central Americans who come to the U.S. on foot. We must accept that Trump’s border wall has been built and, ironically, it is invisible… just as he incoherently promised.

For anyone who has not drunk the Trump Kool-Aid, it is beyond obvious that this president is obscenely and dangerously racist. His gross disregard for the human rights of asylum seekers is only matched by his total disregard for the constitutional power of Congress to keep his absolutely corrupt use of power in check. His lawlessness poses a danger to the rule of law—the very reason Central Americans still opt to come to the United States, leaving behind their own lawless countries. Because of Trump’s xenophobic policies, thousands of people will painfully and silently die in Central America. Our humanity is at stake. What now? Let us all look up to Manuel. Since becoming an American citizen, he has not returned to the shadows. Unlike many immigrants, he has not selfishly called for the door to be shut right behind him. He now has an extremely important position at the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant where he works closely with refugees from Latin America. He educates them on financial literacy, informs them on their rights as tenants, asylees, and members of our American society. He is a tireless and passionate advocate for their rights. Manuel has a beautiful poster of Monseñor Romero in his office; it is his own source of inspiration. Romero’s last sermon rings just as true today as it did in 1980: “I beg you, I plead with you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression.” We must confront the repression embedded in the laws of this lawless president through civil disobedience. Fife and Schultz have shown us how.

Aria Fani is an immigration rights advocate and assistant professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization at the University of Washington.