By Aria Fani

Last December, when I decided to offer a literature course in the spring on travel and social encounters at the University of Washington, I had no idea that I would be teaching online while living under a lockdown. Teaching at home made for a potent irony, reading and thinking about travel during a time of severely restricted mobility. I have taught travel literature twice before and I always make sure to mention that travel is not limited to people with disposable income. In fact, it is the displaced and the dispossessed of the world who do most of the traveling. For them, there is a human cost associated with mobility. They have to overcome multiple barriers and borders to make themselves visible to legal systems and navigate their bureaucratic labyrinth to safety, or alternatively, hide from legal institutions in fear of deportation or incarceration.

Experiencing a nation-wide lockdown is probably as close as many of us will ever come to understanding a world in which mobility cannot be divorced from grave risks. During the stay-home order, we all had to leave the house at some point because not eating was not an option. I seized on this experience to remind the class that staying put is simply not an option for millions of people who are displaced by war and conflict—for many of them, home is simply a death sentence. One documentary that shows the true cost of mobility is Rebecca Cammisa’s Which Way Home (2009). It follows a group of unaccompanied Central American minors who are fleeing broken homes and an ecology of criminal impunity to seek a better life in the United States. As Valeria Luiselli has so eloquently put it in Tell Me How It Ends (2017), they are not coming to steal your American dream; they are just trying to escape the nightmare into which they were born.

Which Way Home captures some of the dangers these unaccompanied minors from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have to overcome on their way to the U.S.-Mexico border. They have to overcome extreme hunger and thirst, physical injuries as a result of walking long distances, the rampant criminality of Mexico’s federalist police, the general xenophobic climate of Mexico toward Central Americans, armed drug cartels who prey on them, and—if they are lucky enough to make it—a desert with a deadly heat that separates the U.S. from Mexico, as well as a racist administration in the White House determined to continue using dark-skinned immigrants as a scapegoat to cover its own political corruption and thievery. These minors traverse the length of Mexico by jumping on the roof of a network of freight trains infamously called La Bestia or the Beast. La Bestia has maimed and killed hundreds of immigrants over the years. You would be hard pressed to find a more potent metaphor for the human cost of mobility in many parts of our world.

Which Way Home is a very powerful documentary; there is no narration or expert commentary by some stuffy historian of Central America. Of course, the documentary is still mediated by what the cinematographers show us (and do not show us) and the questions they ask these minors along the way. But you still get a nuanced, real sense of what mobility means to a group of Central American youths who grow up in extreme poverty, brought up by parents who have not had the chance to address the collective trauma of long and brutal civil wars that were supported and funded by the United States of America. I show Which Way Home on the last day of class because it offers us an opportunity to separate travel from tourism as a modern industry and question the discourses of power that govern the composition, publication, and circulation of every travelogue we read in class.

Since I thoroughly enjoyed teaching this course, mainly thanks to my insightful students, I have selected some of the texts to make a summer reading list for my Peyk readers. I only plead with you not to buy any of these books on Amazon. Boycotting a mega-corporation because it benefits from a deadly pandemic, pays no taxes, spends unlimited cash to buy influence in politics thanks to our broken democracy, and abuses its workers is not a long-term strategy. But in the absence of a Congress willing to address our broken economic system that allows for and actively facilitates such immoral accumulation of wealth (Jeff Bezos is said to be on track to become the world’s first trillionaire by 2026), then boycotting will sadly have to remain in our strategic arsenal as progressive-minded consumers. Please consider supporting bookshop.org or your local bookstore by purchasing the books on this reading list.

The Travels of Ibn Battuta (Translated by Sir Hamilton Gibb and C. F. Beckingham and edited by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, 2003)

This work was originally composed in Arabic and entitled Tuhfat al-anzar fi gharaʾib al-amsar wa ajaʾib al-asfar or “A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling.” Born in Tangier, Morocco, in the early fourteenth century, Ibn Battuta is without a doubt the most celebrated Muslim traveler. He undertook a series of breathtakingly long travels from his hometown of Tangier to Far East Asia, the eastern coast of Africa, and the Indian Ocean. The outcome of his travels was a detailed ethnography of post-Mongol Muslim lands, their urban centers, cultural practices, linguistic make-up, and luminaries.

What would be of interest to Peyk readers in particular is Ibn Battuta’s travels in Anatolia where he visited Konya and talked about a certain Jalaluddin (Rumi) who had created the Persian rhyming couplets—a text that, according to Ibn Battuta, was deeply studied and commented on at the time (Ibn Battuta was born some three decades after Rumi died). Ibn Battuta actually went on to learn Persian during his travels and even served as a judge in the court of Muhammad Tughluq in Delhi where Persian was a language of political administration and cultural production.

Nasir-i Khusraw’s Book of Travels: Safarnamah (Translated by Wheeler M. Thackston, 2001)

This is the first major travelogue or safar-name composed in New Persian in the eleventh century, the literary language that emerged after the advent of Islam in the ninth century. Naser Khosrow (a spelling that more closely reflects the Iranian pronunciation of his name) worked as a financial secretary and revenue collector for the Jughra Beg, the emir of Khorasan. He decided to abandon his courtly station and go on Hajj. Our modern-day expectation of a travelogue written for the purpose of pilgrimage is devotional or spiritual. But we need to remember that prior to the rise of tourism, pilgrimage was and continues to be one of the most major forms of population mobility. Ibn Battuta and Naser Khosrow both state in their travelogues their desire to visit Mecca, but this intention does not in any way exclude their desire to visit major urban areas and expand their courtly and scholarly networks by spending time in those cities.

Naser Khosrow’s Book of Travels is written in a very clear and cogent Persian prose. Naser Khosrow was also a very skilled poet and has a collection of highly philosophical poems in Persian. But we do not see his philosophical side in his travelogue. Instead, we meet a traveler who observes unemphasized details in architectural monuments, delves into irrigation techniques used in Egypt, and carefully documents the dates and distance of his travels from Saljuq Khorasan to Fatimid Cairo, a journey that took him seven years to complete. His travelogue may seem uninteresting to some given our modern-day expectation to see an autobiographical or introspective voice in travelogues. But once we adjust our expectations, we see a brilliantly insightful travelogue that gives us access into the urban structures of eleventh-century Muslim lands. One lingering mystery about Naser Khosrow’s travelogue is the fact that there is no mention of the pyramids at all. Go figure!

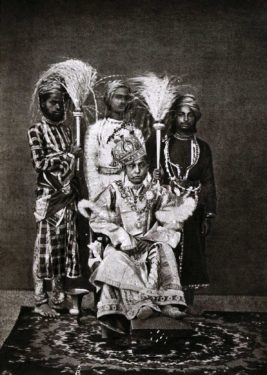

A Princess’s Pilgrimage: Nawab Sikandar Begum’s A Pilgrimage to Mecca (Translated by Emma Laura Willoughby-Osborne, 2008)

Tārīkh-i safar-i Makkah, translated into English as A Princess’s Pilgrimage, is the account of Sikandar Begum’s journey to Mecca in 1863-1864, composed originally in Urdu in 1867. Astonishingly, Sikandar Begum is the first Indian ruler to have gone on Hajj. The challenges of making the pilgrimages were so extreme that rulers usually avoided making the journey themselves. Sikandar Begum was a ruler of Bhopal, a nominally independent region in British India. She was a just ruler and a patron of arts and culture.

Her British friends encouraged her to document her journey in writing as they thought it would make for a compelling read in the UK. In 1863, Sikandar Begum left India for Mecca with a retinue of a thousand people. In making the Hajj, she showed her strong connection to her Muslim faith and established her credentials as a worldly and accomplished ruler by doing something that her male predecessors had not done. The travelogue is fun to read and contains the author’s candid and sometimes highly critical assessment of mid nineteenth-century Arabia, its urban people and rural tribes, its slave markets, and cultural practices.

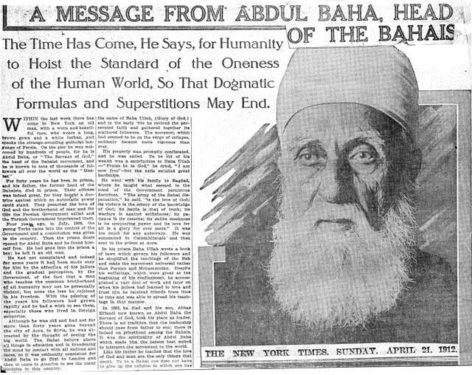

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá Travels to North America

Born as Abbas Efendi (1844-1921), ʻAbdu’l-Bahá was the eldest son of Baháʼu’lláh. He served as head of the Baháʼí faith from 1892 until 1921. He lived under house arrest in British-mandate Palestine until the revolt of the Young Turks against the Ottoman sultan finally gave him freedom of movement when he was 64 years old. Invited by the Baháʼí community of the U.S., he visited the United States twice between 1911 and 1913. On April 11, 1912, he began an eight-month journey to North America. During his stay, ʻAbdu’l-Bahá gave 373 talks in the U.S. and Canada to a cumulative audience of more than 90,000 people. ʻAbdu’l-Bahá did not leave behind a personal record of his many lectures, but some of them have been transcribed in Persian while others have been documented in English translation. You can find them in The Promulgation of Universal Peace (Baha’i Publishing, 2012). You can also access those lectures in audio format at centenary.bahai.us.

ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s travels in North America were relevant to my course for a number of reasons. A recurring theme in class was the problematic history of assigning a single essence to large cultural entities. We have all heard (or even uttered) the cliché statement that “the East is the land of philosophy” or “Iran is the land of poetry.” One of the pervasive stereotypes of the so-called East in early twentieth-century U.S. would have been the East’s association with mysticism (as opposed to the West embodying rationality). ʻAbdu’l-Bahá physically fit that stereotype, a man speaking an exotic tongue with a long white beard. But the content of his message defied any single stereotype. He lectured on the question of social justice, officiated the first interracial marriage of an American Baha’i couple, insisted on being seated next to his black companions in white gatherings, and called on the U.S. society to address systemic racism. One can imagine that many would have been taken aback by an Eastern man lecturing the U.S. on social justice. The fact that an Iranian traveled so extensively in the U.S., spoke to hundreds of Americans in different urban areas, and received press coverage at a time when no Iranian communities existed in the U.S. is itself deeply intriguing. Unfortunately, very few non-Bahá’i Iranians seem to have heard of the story of ʻAbdu’l-Bahá’s travels.

If there is one key lesson to take away from these readings, it is the fact that humans have always been on the move. Travel and mobility are not unique to the age of globalization. In fact, when one views our history at a macro-level, one quality that emerges as fundamentally human and socially pervasive is movement. This is precisely why any ideology that assigns a proper place to humans, languages, and religions boils down to one common denominator: erasing and reducing patterns of human mobility. White nationalists in Europe sell the fiction that there was once a Europe empty of Muslims to which white Europeans can now strive to return. Hindu nationalists in India frame the military campaigns of Mahmud of Ghazna as an invasion of “foreigner Muslims” who invaded and ruled over “Hindu India.” Iranian nationalists obsess over the historical migration of a semi-nomadic group called Aryans who are credited to have created an early civilization in the Iranian Plateau.

Let me be absolutely clear: I do not deny that Mahmud made military inroads into India or that some tribe settled the Iranian Plateau at some point in history. There are historical and archaeological documents that prove, to varying degrees, both of those events. Here, I want us to think more critically about why there is so much importance—bordering on obsession—placed on locating and celebrating a pure origin story for the nation or its invaders. Before nationalism, in a world with no nation-state borders—where the relations between ethnicity, land, language, and origin were deeply complex and non-linear—what does it mean to speak authoritatively about a group of “foreigners” ruling over India or Aryans constituting a people “starting” a new civilization that we as Iranians have learned to claim as our “own.” You are welcome to disagree with my assessment. But I still want you to imagine a world of movement in which ideas of “insider” and “outsider” were in constant flux and there was no singular or proper place to which humans, languages, and cultures belonged.

You may reach Aria to ask for the entire reading list: ariafani@uw.edu

Aria Fani is an assistant professor of Near Eastern Languages at the University of Washington, Seattle. Reach out to him at ariafani@uw.edu.